32: Pristina

Biennialization and hyperculture; the decolonization of time, dissolution of borders, reimagining of socioecological space, and plural flourishing of more-than-human dignity, or,

the everywhere perennial of quotidian kindness and beauty.

The major international, durational and discursive survey of contemporary art is a variegated and contested site for the rehearsal of socioecological relations and cultural exchange becoming-commensurate with a scale of concerns responsible to an interdependent planet. Looking at particular situated instances of critical biennials, quinquennials and the like, is an instructive practice for reimagining relationships to knowledge production, time, labor, place, education, and leisure, while identifying practices worth developing and reproducing. This includes the occasioning of ongoing symposia, installations, libraries, performances and other forms of in-person and online sociality, as well as print and digital archives and publications.

As contemporary art, modeled on an eurocentric and market-driven approach, inextricably linked to colonialism, has reflexively included into its machinations an autocritical tendency, as well as assimilating social and relational practices into the ocular-centric Visual Art Exhibitionary Complex (Smith, 2022) and coevolving with the precaritization of labor resulting in the turn towards platform capitalism and the ever encroaching financialization of all forms of life—particularly under neoliberalism, it has opened up durational occasions for critical reflection on the production of these practices through the extended biennial form, which has rapidly proliferated since the latter half of the 20th century and is characterized by the production of live and discursive events—unsettling the hierarchies of received exhibitionary teleologies—and perhaps suggesting what Sianne Ngai formulates as the becoming-ergon of the parergonal discourse of evaluation. (Ngai, 2020, p138)

The pedagogical turn in contemporary art, owing in part to internet-restructured forms of knowledge production, consumption and contestation, in concert with the vocational exodus from the austere conditions of academia and journalism, has further advanced the biennial as a site of discursive exchange and knowledge production, and often with a rigorous criticality articulated transversally through disciplines and contexts. Though perhaps more than transversal in effect, it is an articulation of a hyperculturality that ‘de-facticizes, de-materializes, de-naturalizes and de-sites the world.’ (Han, 2022, p79) distinguishing itself from the modern tendency of essentializing regional cultures—prerequisite for thinking trans— or inter— relationships to begin with. The peripatetic class of art elite is a pronounced articulation of these effects that can also be readily observed in the hypermarket diversity of globally connected locales, their various marketplaces, and the windowed ontologies of tabular internet browsing.

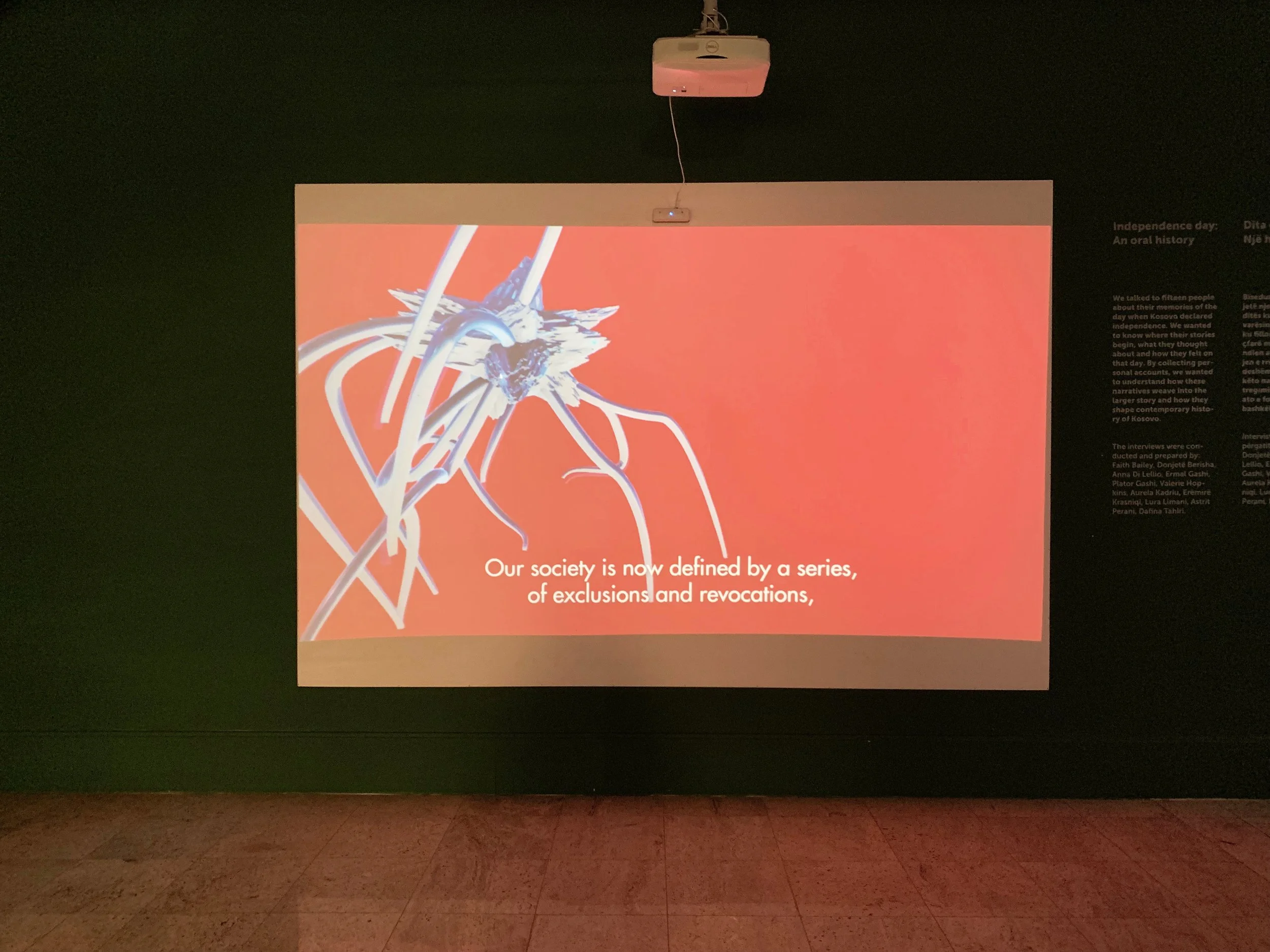

In an ever-implicating globalized interconnected world of collapsing distance and horizon, in the midst of cascading socioecological crises, we find an imperative to create and gather in de-virtualized social spaces for apprehending and addressing our mutual concerns. Additionally, the practice of this kind of unevenly accessible, planetary being-with produces affirmative models for reimagining public space and relations, with an abundance of cultural offerings and the conditions for what we might call reparative sociality. What is abundantly clear in any conversation about this kind of exhibition-making, is the necessity to better distribute time so that the many strata of working classes can participate in not only the ethically-concerned and aesthetically manifold sociality of this kind of exhibition-event but also, and more significantly, to determine the use of their time towards their most meaningful relations and vocational calling. This would involve a radical restructuring of the expectations and protocols of work, towards a dramatically reduced imposition of coercive waged labor and greater access to social services, education, health care and mobility. The affirmative dimensions of SICAS and the ongoing struggle for social and ecological justice, while embodying tensions, can exist as compliments.

The term ‘biennial’ has come to stand in for a spectrum of large-scale international durational exhibitionary happenings that occur with increasing volume around the world. It is a misnomer, however, as in many cases they happen with differing intervals and the reference to the time in between their presentations doesn’t account for their qualities. I offer in its place the Seasonal International Contemporary Art Survey or SICAS. Seasonal connoting their time-bound durations and recurrent structure, and survey including the discursive function left out of the visually-privileging exhibition.

The documenta, a quinquennial survey, is a useful case study to sketch out some of the claims and potential horizons of the form. Inaugurated after the second world war in Germany to exhibit formerly censored ‘degenerate art,’ the documenta has grown over the subsequent 15 editions to rehearse a number of different formats, methods and modes of production and distribution. Since inception, it was billed as a pedagogical survey that has increasingly folded more into its curatorial purview. Enwezors 11th edition marked a significant departure from the occidental focus of previous editions and was produced in 5 different locations with a range of artists, many from the global south—if not capitulating to familiar formats dictated by western markets and conventions (Documenta11 - Retrospective, n.d.). Coterminously, roving SICAS like Manifesta moved towards peripheral European contexts while the general global proliferation of SICAS has occasioned differentiated forms of multilateral hybrid cultural exchange often focusing on concerns outside of, or resisting, Euro-North American chauvinism, including in Sao Paulo, Havana, Istanbul, Gwangju, and Dhaka.

SICAS are highly variegated in their production and distribution and have justly been criticized for their nationalism, neoliberal dispositions, interventionism, orientation towards tourism, and at times, collusion with oppressive state apparatuses. These compromised states, which has been well documented by critical historians like Charles Green, Anthony Gardner, Maria Hlavajova, Simon Sheikh and many others, does not obviate the potential horizons of these survey-forums, which are likely immeasurable in their extensive, relational, cultural impacts over times. Simply looking at one documenta, especially one located in multiple cities, for 100+ days of live events, installations, screenings, publications, and so on, demonstrates the impossibility of the apprehension and synthesis of an event which is experienced in so many ongoing, unfolding, anasynchronous ways, as well as through the tertiary and further refracted speculative possibilities collaboratively constituted with what Filipa Ramos terms the absent spectator—those who engage with the mediated remainders and echoes of the event (Verheaven, 2021). This last historiographical effect is deserving of further exploration, and is being reconfigured in an age of exponentially multiplied, instantaneous and indexable media circulation.

As Maria Hlavajova observes,

‘the history of exhibitions mounted by any one biennial institution (think of Manifesta or the Berlin Biennial, for example) must therefore necessarily be the history of separate, independent, unrelated, eccentric, disparate curatorial projects that are in fact often brought to life through a principle of opposition to previous editions or even through a strategic denial of what has been done before. Thus it is relatively common that if the past (in other words, previous editions of a given biennial) is in any way present in new biennial iterations, it is brought about through the trope of negation. Add to this the establishment of short-term, temporary, and, to the greatest extent possible, exclusive alliances with the figure of the curator, from whom the biennial borrows his or her fame, knowledge, networks, etc., only provisionally, and the identity of the biennial must necessarily be unstable, always in flux, and difficult to articulate in terms of continuity or as something more than just the sum of its editions over time.’ (Basualdo et al., 2010, p295)

Rather than looking at these events as somehow separate and detached from their immanence, it is perhaps more generative to view their transmigrations through mediated time as a thickening of relational multiplicities, stimulated and encouraged by particular SICAS and their long durée mixed-modal dissemination.

An inventory of the constituent elements required for occasioning art—with the capacious, partial and fugitive definition operating here—can most basically be understood as subjects, objects and times, the latter being of primary interest and where the stakes of this thesis are most concerned. This broad understanding of art invites the open question of conditions favorable to art as always already provisional and co-determined, and foregrounds relational discursivity and transmigrating affects and dispositions against the backdrop of aesthetic objects that occasion these relations. A city like London, where I’m currently residing, has in excess many of the conditions favorable to art and the offerings one encounters in SICAS—namely, the ongoing superabundance of aesthetico-social events. It suffers, more acutely, from an austerity of time among the working classes and simultaneously—and very qualitatively differently—a cultural excess among the elite and more time-privileged, for whom it is impossible to enjoy the scope of this overwhelming superabundance, accumulated largely through the violent dispossessions and subjugations of capitalist colonial empire. Put simply, a more even distribution of agential time is needed as a prerequisite for any conversation about exhibition-making and audience-participants.

These themes are taken up recursively in many SICAS, which tend to feature fertile interdisciplinary and transmedial assemblages that, to my mind, are without comparison. The critical biennial is proving to be a generative site for explicitly redressing violent histories of power relations and rehearsing the otherwise in explicitly inter-cultural exploratory milieux, while it remains to be seen—and is hard to measure—the extent these experiments migrate into culture more broadly speaking. Here it might also be useful to examine the word rehearse, which is popular in the contemporary art lexicon and in my usage connotes the preliminary suite of gestures towards the counter- or alter-hegemonic, from which to build more lasting physical and social—or perhaps even what Irit Rogoff calls spectral—infrastructures, suggesting the axiomatic habits of mind that condition and choreograph relations.

Another infrastructure of great interest, that we might term a deterritorialized, or perhaps simply a truly territorialized—in the broadest sense—infrastructure, is e-flux. Mirroring and producing a global art world, e-flux is like the central nervous system of contemporary art, not insignificantly started by artists, and holding some similar tensions of a market-dependent position seeking to overcome its contradictions and conditions towards a more socioecologically just world. This is made apparent through its editorial purview. It is largely through e-flux that the art world apprehends the mediated contours of its global reach and elaborates its themes.

This year, documenta’s Jakarta-based artists’ curatorial collective ruangrupa has built the foundation of their documenta fifteen on the core values and ideas of lumbung (an Indonesian term for a communal rice barn). Lumbung as an artistic and economic model is rooted in principles such as collectivity, communal resource sharing, and equal allocation, and is embodied in all parts of the collaboration and the exhibition. (Documenta Fifteen, 2020). ruangrupa invited 14 other collectives who in turn are working with around 50 collectives who have invited over 1500 artists to participate in this experimental form of more-than-exhibition making. Most of the artists operate in contexts outside of Western Europe and North America and have brought to Kassel innumerable histories, perspectives and objects to exchange and co-create art with. The first week of documenta had 250 events planned, many of which were canceled due to Covid concerns. An unfortunate oversight regarding antisemitic characters depicted in a large mural made by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi in 2002 has, at the time of writing this, dominated the press coverage of the event, though not deterring the half million visitors that have gone to engage with this diverse presentation at the halfway point of the exhibition (Arruda et al., 2022)

When I arrived at documenta I encountered Le18, a collectively-run Marrakech-based community arts space, library and film archive that was invited to participate. They had expressed their misgivings about the expectations to exhibit something and instead provided a convivial and welcoming space for reading, watching, reflecting and conversing. It sat nearby a community garden, planted and maintained by the Nhà Sàn Collective from Vietnam, along with a seed library, some drawings and beautiful film by Quynh Dong. A handwritten sign informed us there was a time we could return for a free haircut and a sauna. There was a covered outdoor salon space with comfortable seating and beautiful rugs that hosted planned and impromptu conversations and events. The lumbung program was spread over 32 venues that engaged the hosting city, using it as a laboratory for experimenting with different forms of cultural exchange. One might find it interesting or important to spend a day learning about the suppressed history of the Indonesian mass killings of 1965-66, view an enormous survey of Indonesian protest art, review the initiatives elaborated in a recent symposium on material cycles in the art sector, admire a selection of paintings from a Palestinian collective, visit any number of installations installed in relation to preexisting public and private cultural institutions around the town, drop in on any number of daily talks and events and conclude the day watching a performance in a garden with other interested visitors.

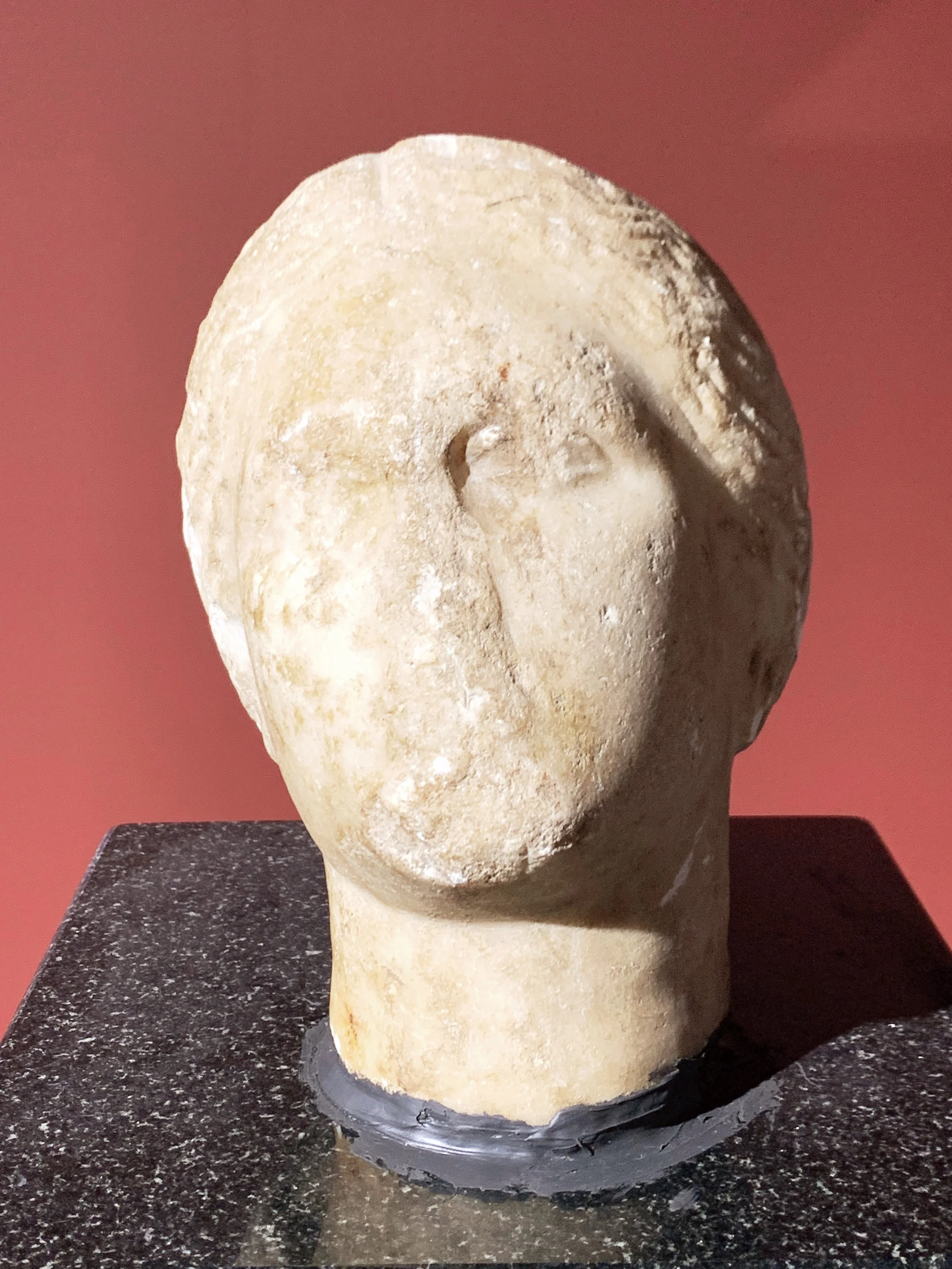

The concurrent Manifesta, It matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise is another example of a comparative cosmological approach, rendered in the phraseology of the influential feminist science scholar Donna Haraway, and also reminiscent of mondialité; a notion of respectful world dialogue from the poet philosopher Edouard Glissant, that is too, often cited in contemporary exhibtion-making. The recent and rigorous Dawn of Everything by the late anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow, unsettle and informedly speculate on received, ideology-saturated master narratives and their social and material remainders. A key text and contribution to a trend we could describe as late modern comparative cosmological composition for the remediation of anthropogenic ecocide.

Cultural syncretism, cosmological promiscuity and hypermarket hybridity are always already present at the crossroads of culture—particularly in urban contexts, and exponentially extend through internet networked technologies—though it is often in SICAS, in operation with other nodes in the contemporary art-discursive matrix, where these features are explicitly named, investigated, and shared through an incredibly wide range of epistemic media.

It's tempting to situate the proliferation of biennials on a continuum starting with the world fair exhibitions, born of triumphalist modernism and colonial extraction in the 19th century. This popular historization is thoughtfully encapsulated by Donald Preziosi in The Crystalline Veil and the Phallomorphic Imaginary essay anthologized by Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal and Solveif Øvstebø’s in their scholarly The Biennial Reader. (Basualdo et al., 2010) It is a fascinating, if at moments excessively Fruedian, examination of the Crystal Palace and its inaugural Great Exhibition of the Arts and Manufactures of All Nations, as the paradigmatic, ‘unsurpassable’ ideological reification and ‘effective vocabulary or medium for imagining nation, empire, ethnicity, and identity in a manner that neutralized otherness whilst simultaneously fetishizing differences as but “stylistic” variations on the same.’ And it is perhaps on this continuum where we could situate Han’s more recent notion of hyperculture and the Crystal Palace’s subsequent extension into virtual space, where the whole of the commodified world, taxonomically-sorted, arrives before the extramodern subject in their very own crystal window. Though perhaps a longer historical scope might better serve us?

In their Unfreezing the Ice Age section of The Dawn of Everything, in the “In which we return to prehistory, and consider evidence for both ‘extreme individuals’ and seasonal variations of social life in the Ice Age and beyond.” subsection, Graeber and Wengrow assemble compelling evidence towards much longer histories of peoples moving great distances, to build temporary, seasonal structures that host diverse gatherings and rituals, and then going further to point out the political dimension that inheres within. While surveying a range of peoples, including those of Amerindian, indigenous Australian, Neolithic Europeans, Göbekli Tepe contexts, they caution against the tendency to inscribe contemporary ideology onto unknowable time-spaces, while concurrently pointing out that “Seasonal festivals may be a pale echo of older patterns of seasonal variation– but, for the last few thousand years of human history at least, they appear to have played much the same role in fostering political self-consciousness, and as laboratories of social possibility.” and put another way, “The really powerful ritual moments are those of collective chaos, effervescence, liminality or creative play, out of which new social forms can come into the world.” (Graeber & Wengrow, 2021)

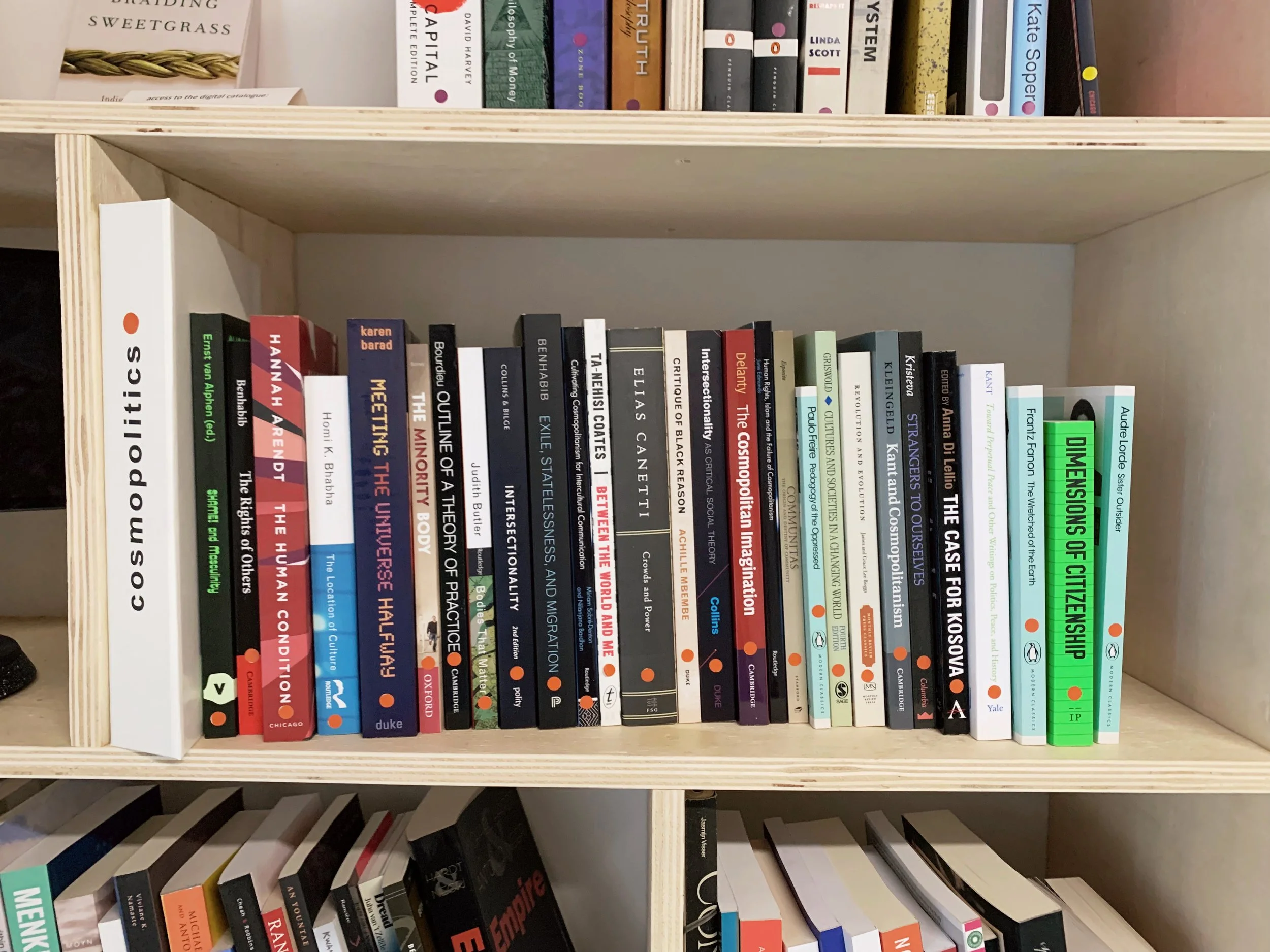

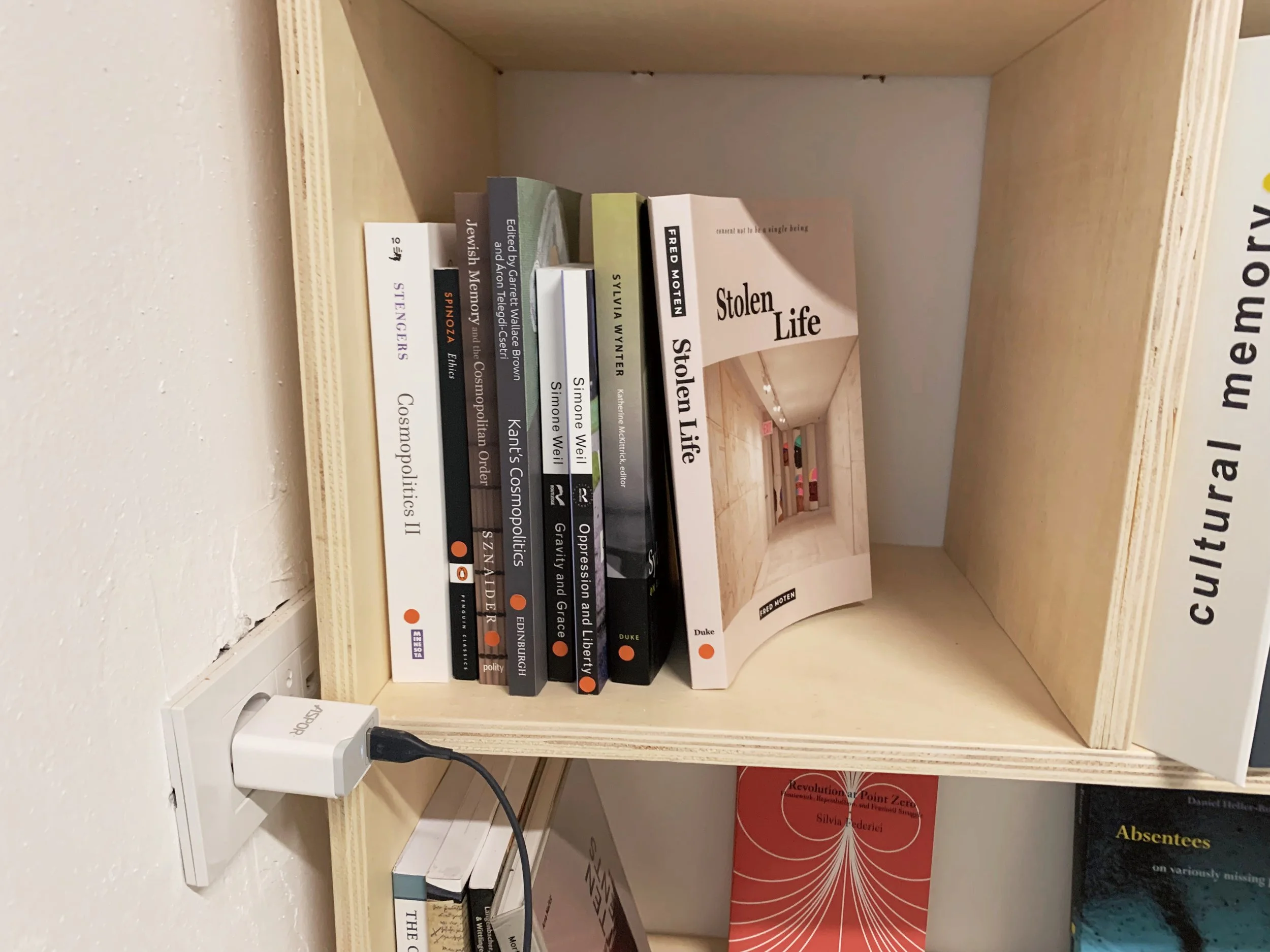

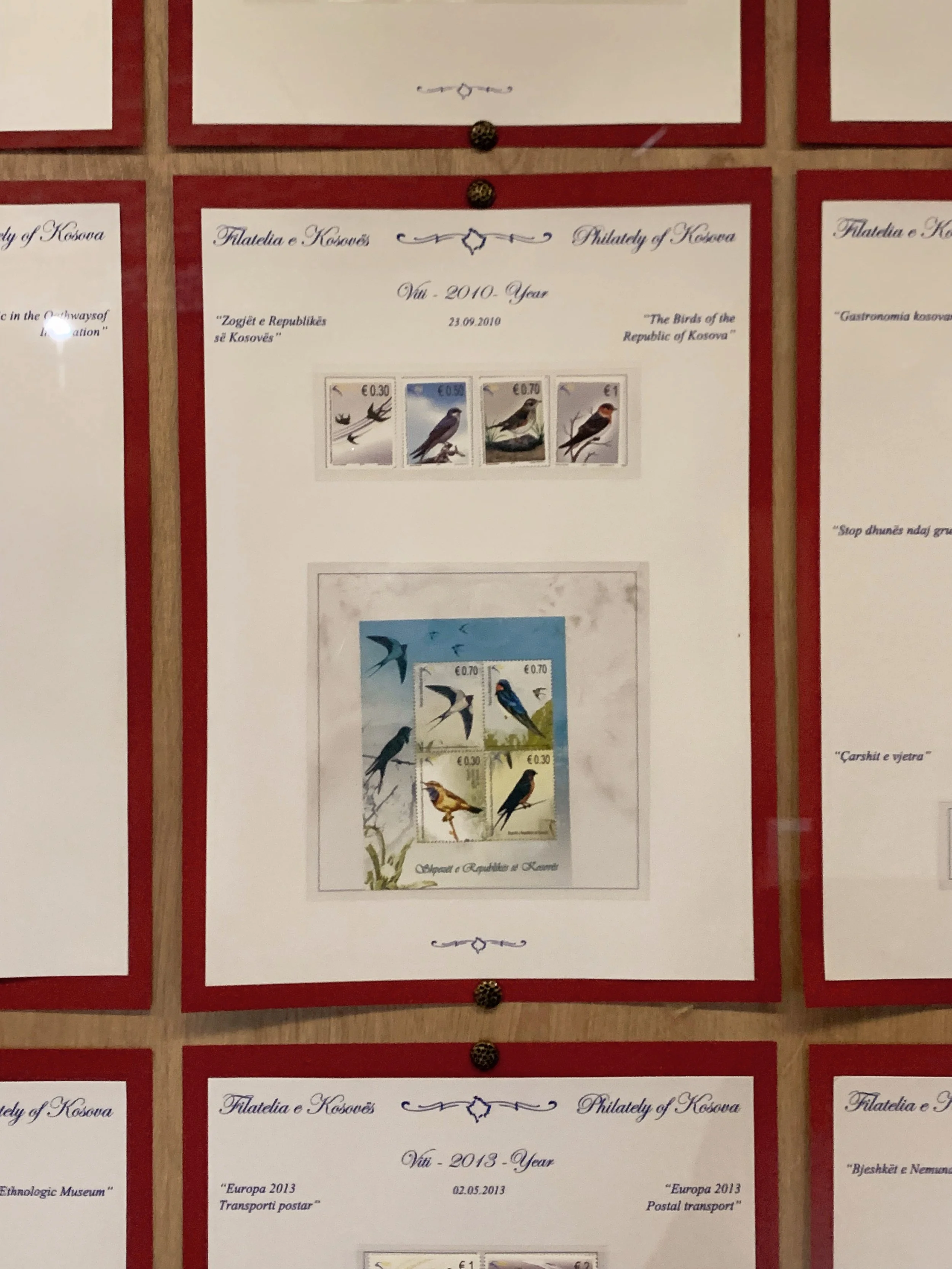

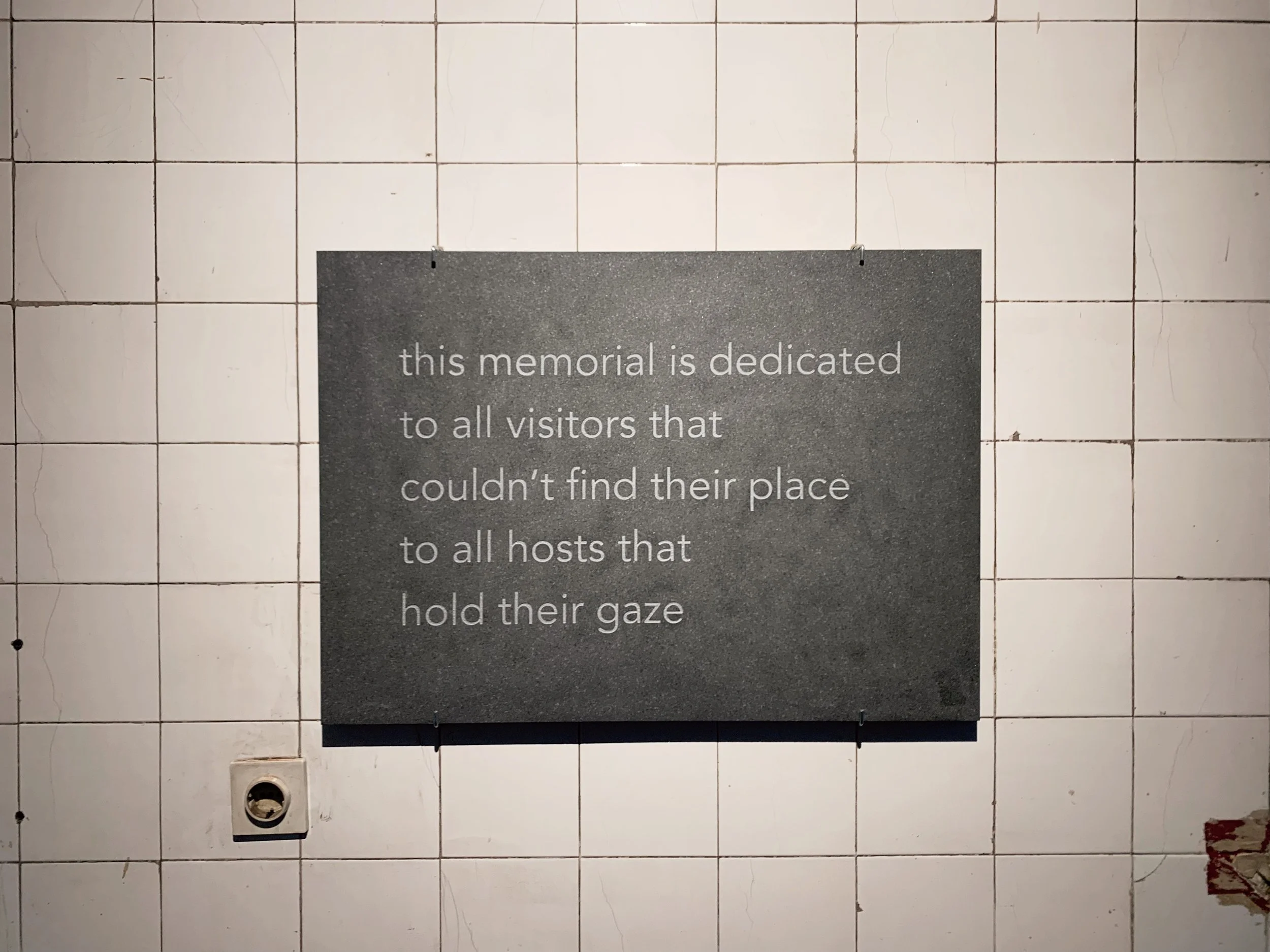

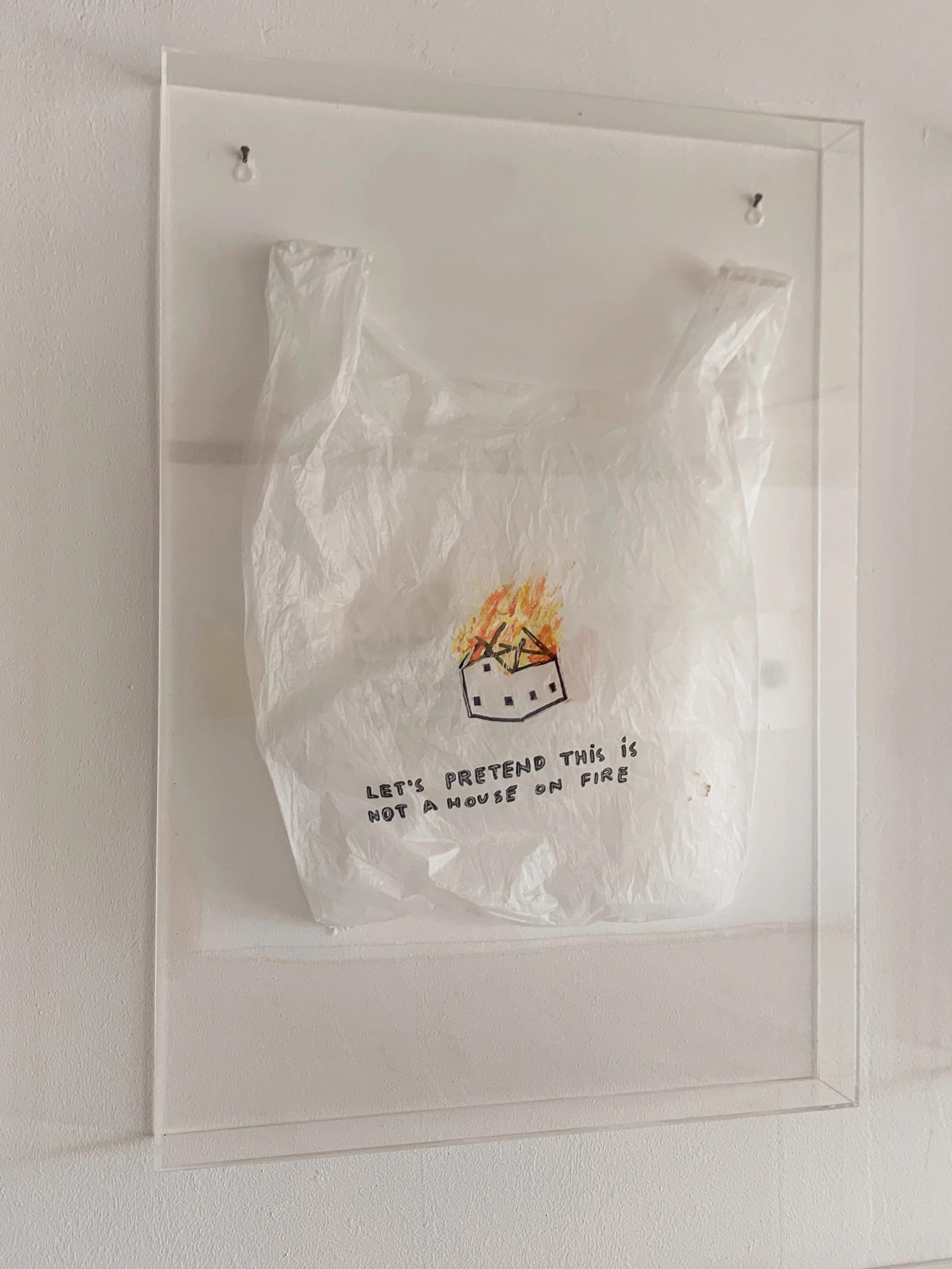

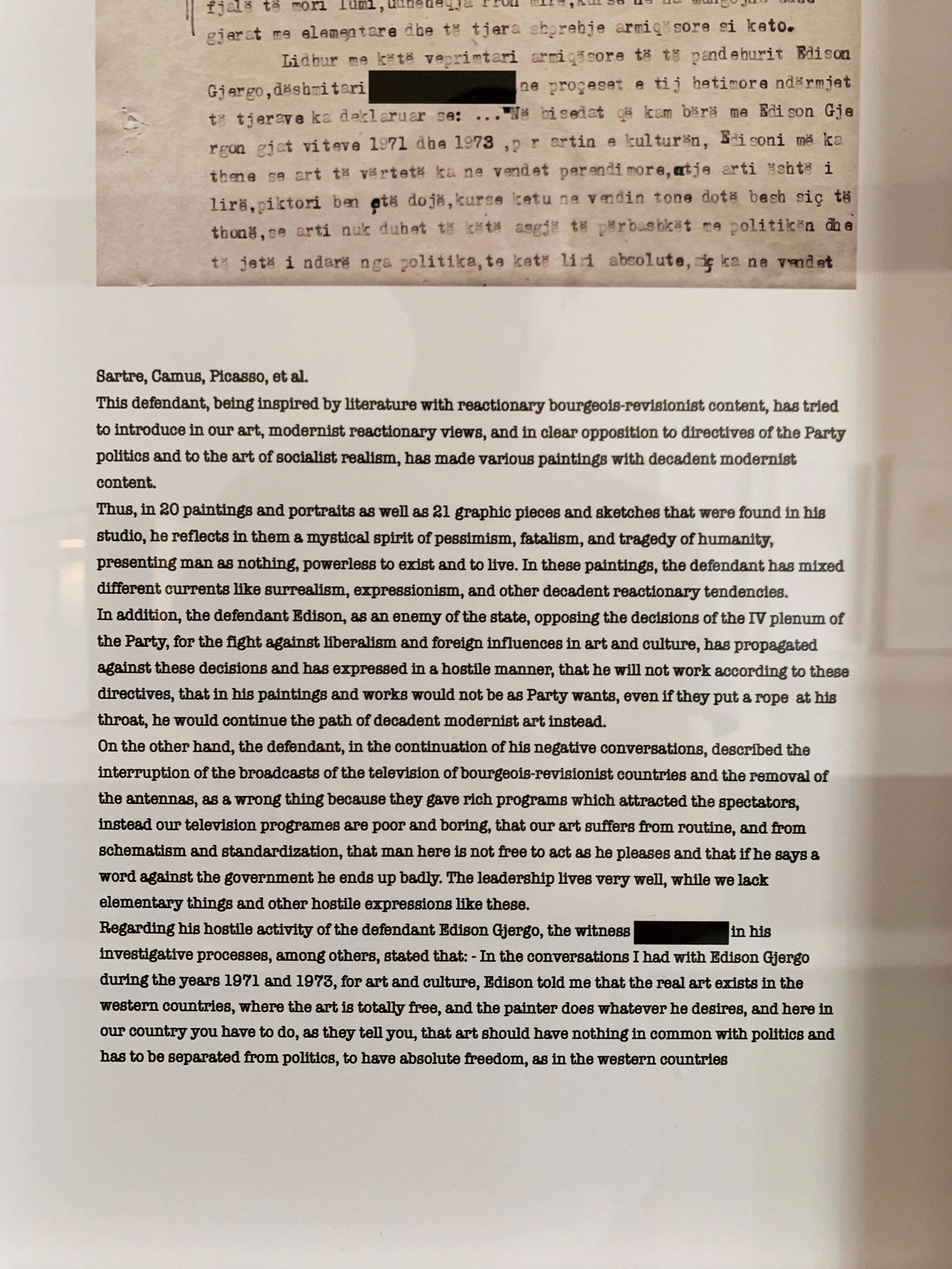

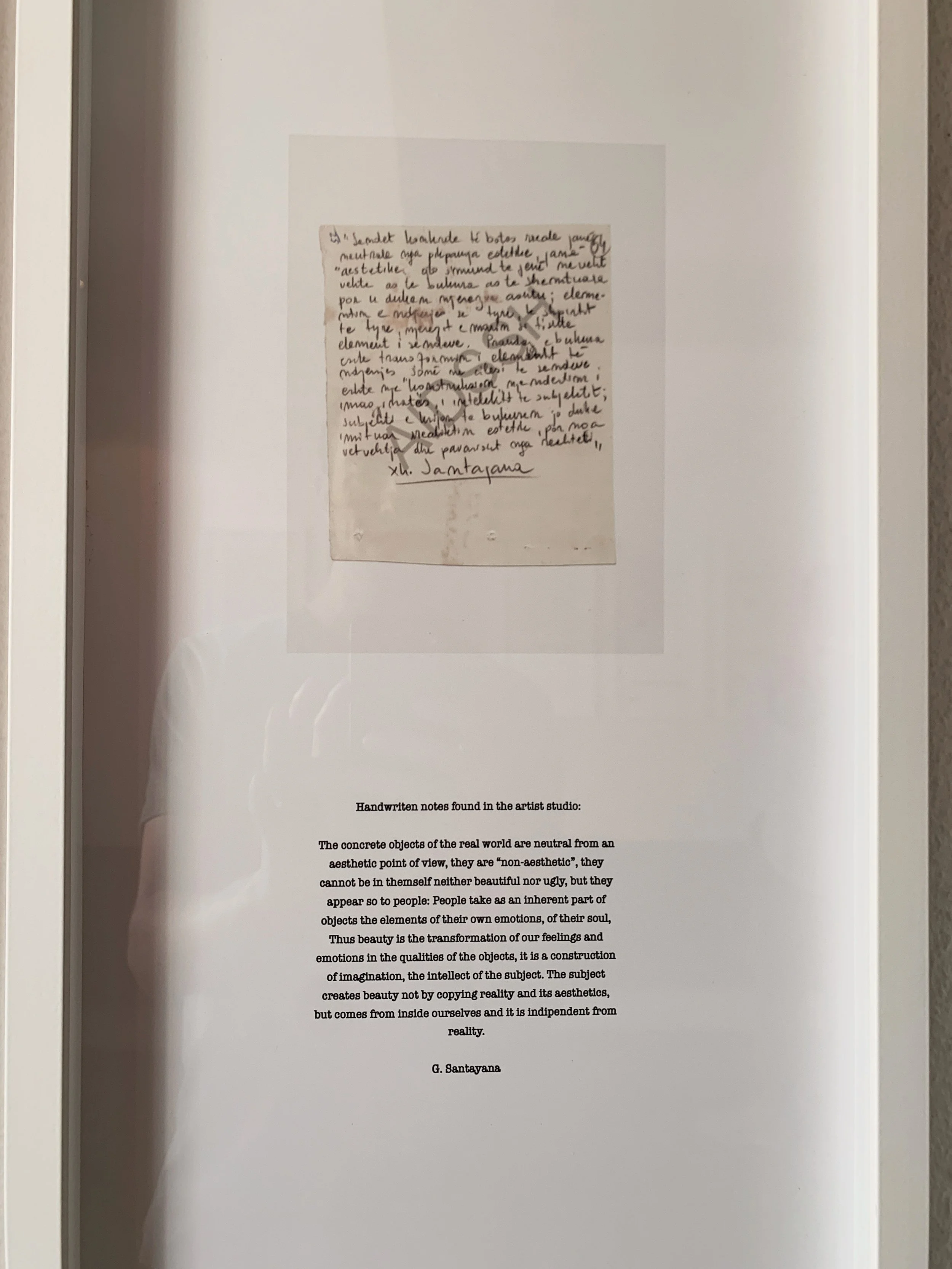

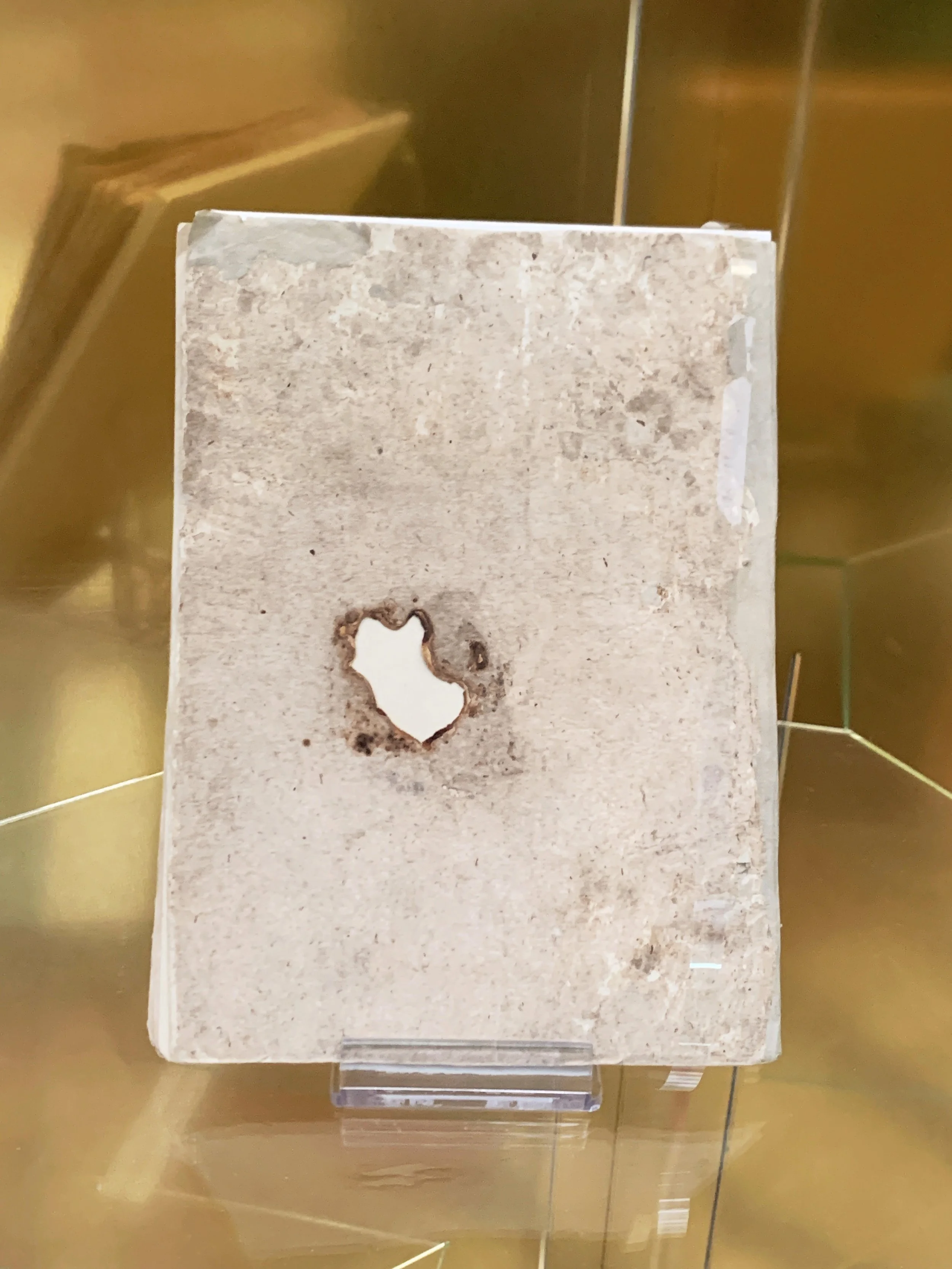

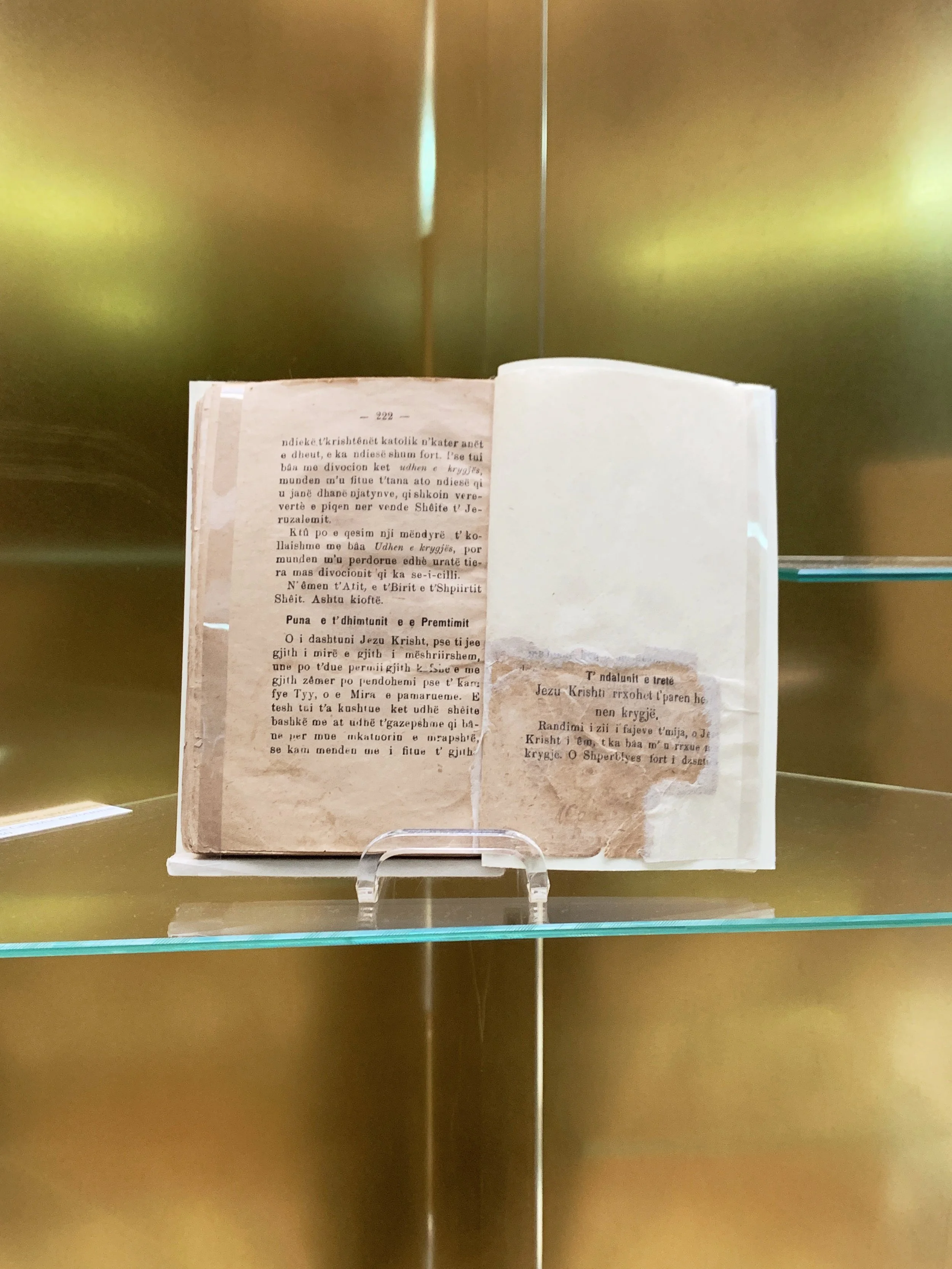

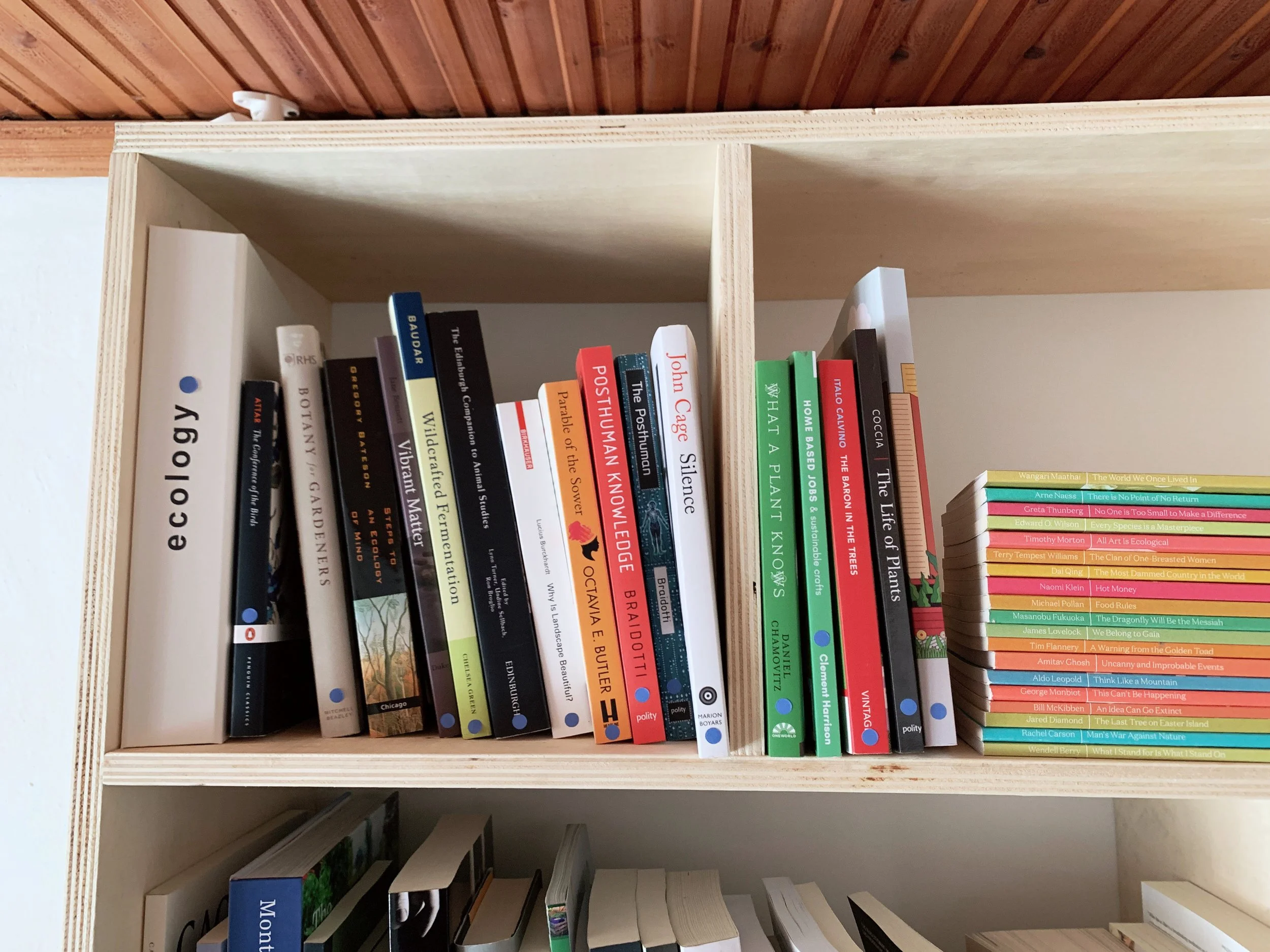

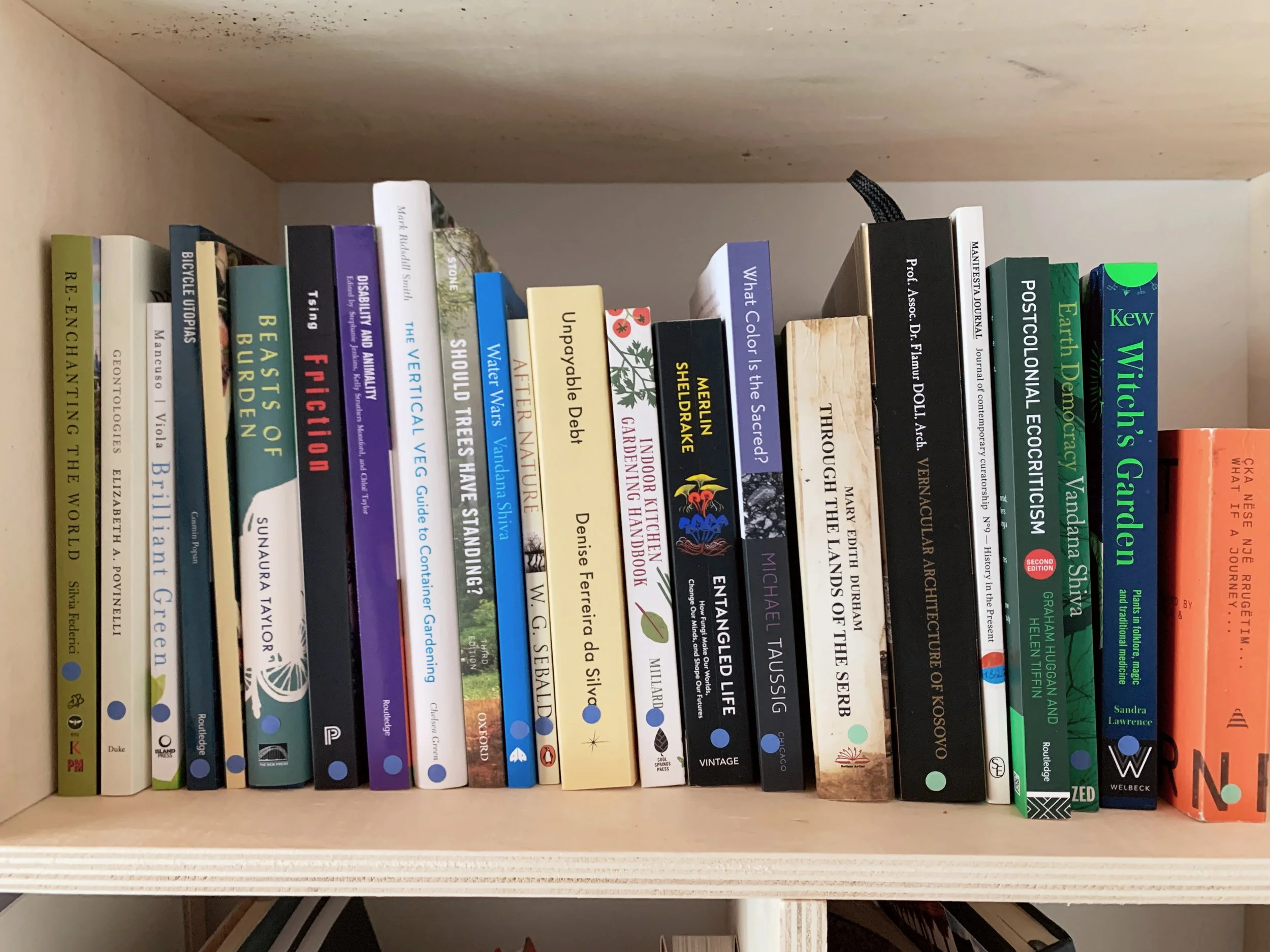

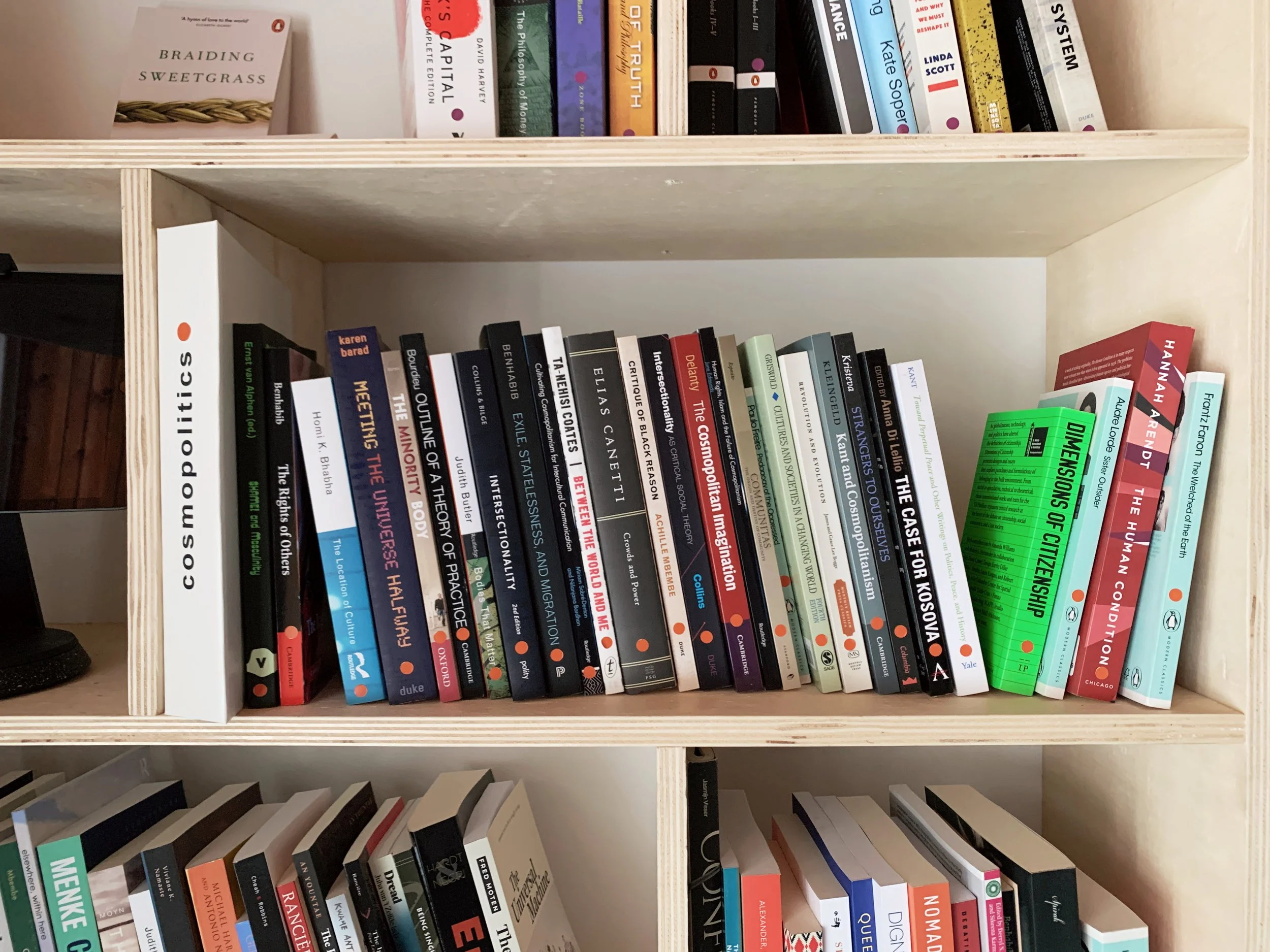

Part of this dissertation is written from the unfolding edition of Manifesta 14 in Pristina. I’m writing at a building that has been used as a residence, library, purportedly a former police administration building, and then left dormant until, at the instigation of Manifesta and with local partners, has been converted into a cultural center with a garden, exhibition spaces, screening room and a thoughtfully seeded library to be developed by the community—and presently cataloged according to sections like cultural memory, cosmopolitics, local history, ecology, and story-telling. The funds raised by Manifesta have been used to rehabilitate the building and it will remain a cultural center after the event concludes. In the Kosovo context, with its deeply felt and immeasurably devastating experiences, economic hardships, structuralized poverty, immobility, cultural loss and amnesia, endeavors to share, archive, restore and create tools for imagining the otherwise, feel compelling.

Manifesta 14 included many regional artists and art spaces, while working with a supportive municipality to preserve and expand public space and facilitate intercultural exchange. In my measure, it felt considered, respectful and appreciated by Pristina at large. As an engaged visitor and researcher interested in understanding the unfolding history of Kosovo, it created intentional and informal conditions for many kinds of learning. The range of visitors with diverse interests and social commitments opened up many intersecting and complexifying dimensions of entangled issues, on an interdependent planet afflicted by financially, politically and culturally constructed divisions. If we approach an event like Manifesta as a site for learning, exchanging, imagining, and experimenting, it shifts the focus away from autonomous art objects, which can better be understood as discursive prompts in an ongoing project of mutual consideration. This affirmative and ambivalent approach should also be considered in relation to the unstated or unintended effects SICAS can have on political and financial agendas and which can vary greatly between contexts and times. In terms of nonvirtual, pedagogical models commensurate with planetary relations, SICAS, and especially thoughtfully-produced ones like Manifesta are a promising form, if not often recuperated by markets and instrumentalized by other actors. The ongoing negotiation of these tensions is one of the crucial tasks for contributors to SICAS.

The notion and process of what I’m calling mediagraphy, and which we might describe as the variegated mediated modes of socialized epistemology, exhibits an entropic quality with technologically-enabled mediums of remediation, effectively adding periods of evaluative latency to a generalized entropic trend. The notion of contemporaneity, built on relative time and conceding the multiplicity of subjectively accessed (and assessed) phasings of times, invites a de-individualizing and relational, technologically-augmented more-than-human dispositional orientation better fitting to a constellative mediagraphical project, that closer approaches the scales in which these massively distributed events in time are apprehended and evaluated.

In lieu of offering a definitive statement on a particular SICAS, I will endeavor to share a present mediagraphy, performing the partial, mediated epistemic practices applicable to this dissertation’s conventions and spatial affordances, and in addition, a range of forthcoming parergonal accompaniments, including an essay film, a visual diary, more obliquely related impressions and whatever other mediated revisitations are to come (add to and amend). I’ve already shared a little of my encounter with the well-established and reflected-on documenta 15, to which my strategic contribution would be mainly to look beyond the disproportionate coverage of the antisemitism allegations towards the 1500+ artists working collectively in predominantly formerly-colonized and oppressed contexts on practicing ways of being and remembering. It also feels incumbent to state that colonial relations, far from being an essentialized binary, are experienced differently across a broad spectrum of interpellating effects and class relations. I’ll focus now on Pristina and Manifesta 14 at greater length, on account of the lesser extent of its available mediagraphy and its vulnerability to cultural amnesia.

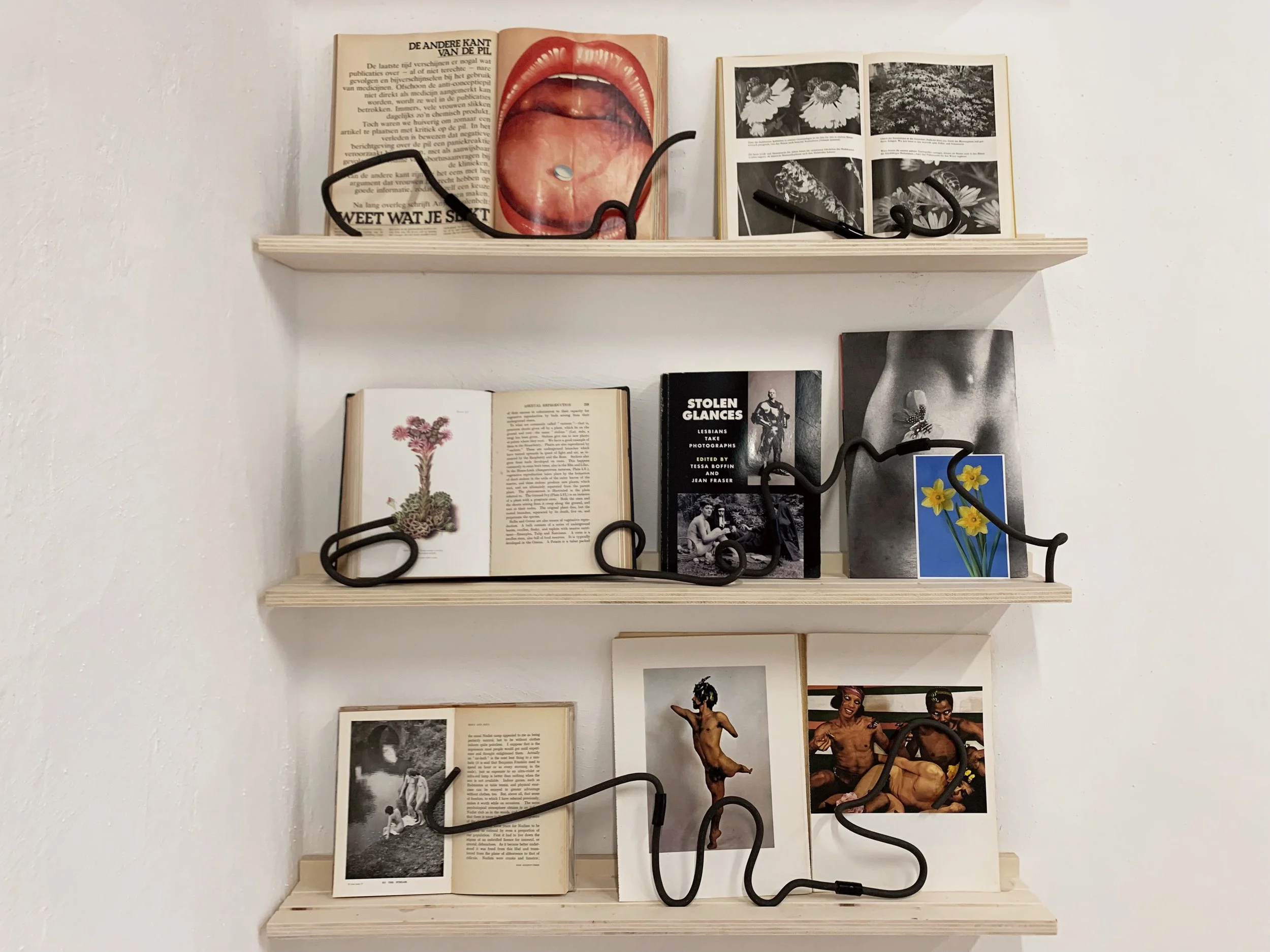

I arrived in Pristina in the afternoon and learned from the Manifesta website about an event happening that evening at the Centre for Narrative Practice. I arrived at a convivial garden, tucked behind a busy street, humming with conversation in the golden-blue evening light. Upon entering the building I was profoundly taken with the selection of texts in their nascent library, skillfully chosen for their influence on the facets of contemporary art we might describe as concerned with developing better relations on a shared planet. Upstairs was a screening room and a number of open studio project spaces that included works in progress and thematic historical archives.

As the event commenced, people took their places in the garden and three local artists began sharing the story of their work and its becoming. The painter Valdrin Thaqi described a childhood memory of a wild horse that went into a fit, and as everyone ran away, they froze and their mother came to their side to watch the mad horse together. This was a formative moment for the artist, who was appreciative of their mothers disposition in parenting, allowing for the witnessing and consideration of unknowable and disturbing events. The evening moved to a nearby cinema, that after many different uses and a period of dormancy, was revitalized by local artists in the community with the support of the municipality—who provided them the space and utilities as long as all the events would be free and open to the public. I learned they also received some cultural funding from other European sources to help pay their operating costs. The screening was a somber short film from a Pristina-born filmmaker, actor and co-owner of some of New York’s most hippest establishments. The evening continued to a nearby street where open air cafes and restaurants clamored joyfully. The filmmaker leaned in over a giant pile of steaming meat and said to me ‘Miss Lily’s to Te Martini.’ I sat next to an actress, artist and cultural worker involved with preserving Pristina’s built and immaterial heritage. She was on her way to London with a Chevening scholarship to study critical theory at Birkbeck. Another actor, rolled up on a handsome bicycle with a clown horn, sat down at a table and introduced the two other people sitting there as my ex and their ex before telling me a little about his short story collection Richard Gere was Here. The group, which I continued to encounter in fluctuating configurations throughout the week, struck me as local ambassadors, providing something like diplomatic relations for a certain kind of peripatetic contemporary art consumer, hungry to engage with curated forms of performative heritage. Though less cynically, I understand our relations to be mostly constituted by shared curiosity and affinities. I suppose what I’m interested in registering here are the distinct class positions that allow for fluency and participation in international exhibition-making contexts.

I approached this Manifesta in Pristina to learn the local history and see what kind of approach and effects this event would have. Pristina overwhelmed me with its warmth, presence, hospitality and sense of lingering time. People seemed decidedly less rushed than in the contexts I am used to. Sociality seemed to be the primary mode of entertainment and there was clearly a strong emphasis on family. The beloved, pedestrianized Mother Teresa boulevard was well used by the community and filled with strolling, talking, laughing, music, playing, eating, drinking, watching and thinking. Perhaps as an enduring inheritance of Ottoman cafe culture, I noticed people of all ages sitting for hours in street cafes socializing. Well into the late evening I would regard three generations sitting together, fully absorbed and enjoying their conversations. There were also farmers markets, outdoor film screenings, and other unrelated-to-Manifesta events happening along the hospitable city center. There were burektore’s every few blocks, serving hot savory pastries and drinkable yogurt for just a euro and change. For me these are examples of socioecological technologies that can be learned from and offer powerful counterexamples to the proliferation of automobilism, western fast food and the rhythms of neoliberal time. The effects on automobilism in particular are devastating and a significant contributor to air pollution, where levels can exceed 400. The marked shift in energy from the pedestrianized city center and the surrounding rings of traffic and coal power plants demonstrate the obvious need to reimagine cities through different infrastructural paradigms.

In the context of this war-torn city, suffering much tragedy and ongoing forms of structural violence, the stakes of this kind of art survey seem particularly high and the responsibility and demeanor as a visitor felt important to consider carefully. As a way into a history I have little understanding of—and from a position as a US (and world) citizen, who is to some degree implicated, the Manifesta offered a site for learning. As such, it provided the occasion and encouraging conditions for intercultural exchange, a program of thoughtful events, and informal spaces for conversations to develop. What I encountered over the week, with all of its wonder, sadness, conviviality and contradictions, will be part of a lifetime of study and an enlarged sense of responsibility to our planetary entanglements.

In a panel discussion called When you talk of the water with Pavel Borecky, Shpat Deda and Prof. Ilir Rodiqi, revolving ‘around ecological issues from the perspective of two filmmakers… that will share their experiences, research and common struggle on the ways that water has depth and breadth politically, culturally, economically and ecologically as a determinant of everyday life’ (Panel Discussion Manifesta 14 Prishtina, 2022) held intimately (and acoustically) during a rolling black-out at the Centre for Narrative Practice, the conversation flowed from ocean acidification to water scarcity in Jordan, to the consequences of hydropower, and into a spirited debate on the differences between infrastructural change and reform positions like recycling and electric cars. It continued into the plaza and over dinner, and likely back to Bern, where Pavel is doing his PhD, and back to London, where I’m writing this paper and perhaps through Pristina and beyond. The lessons Jordan's water crisis can offer to a warming world, as well as the lessons of Pristina’s pedestrianized city center, exemplify the kind of corporeal intercultural exchanges that through their mediated amplification enter into and contribute to our knowledge commons. The practice of rehabilitating unused buildings with the support of public, private and nonprofit partners to build cultural sites explicitly dedicated to free, community-organized programming is another model worth attention and reproduction. As well as affordable and healthy food paradigms like the burektores.

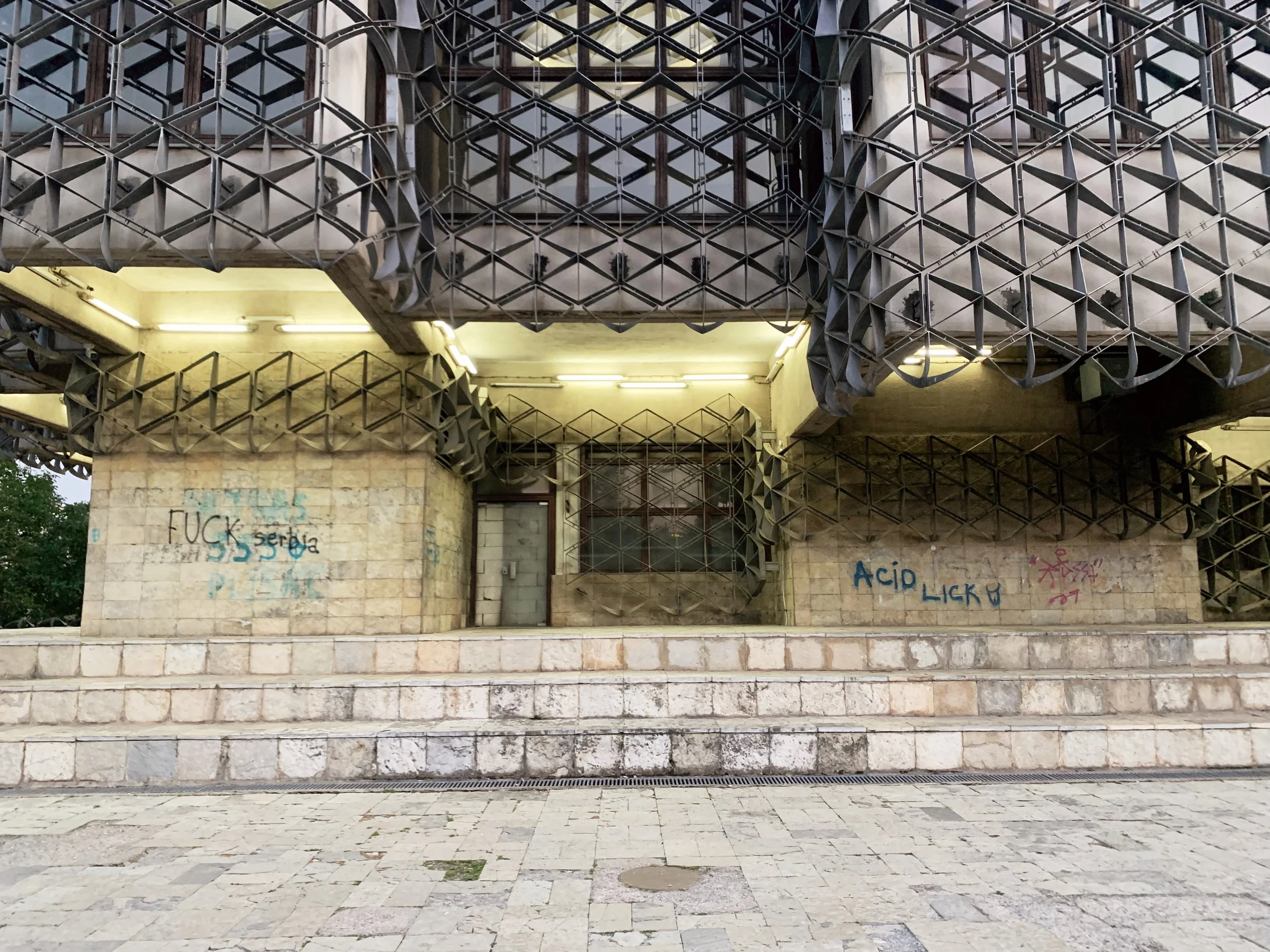

I joined a tour of some of the Manifesta sites that included the Palace of Youth and Sports—a deteriorating entertainment complex build in the mid-seventies, currently partially-privatized and utilizing—much to the dismay of our tour guide—a former playing field as an indoor parking garage, as well as a former brick factory converted into a provisional school and recreation center, a former printing house being used to exhibit an art installation, and an architectural intervention by the Italian architect Carlo Ratti that converted a decommissioned rail line into a bright yellow walking path with some ornamental landscaping. These initiatives elicited a range of responses from our group that included local West Balkan youth, two cultural programmers with the Flemish government, a graphic designer from Leipzieg interested in city-wide temporary design languages, a postgraduate working on issues of colonial extractivism in relation to performance studies, a psychotherapist and filmmaker working with diasporic Albanians and several others I didn’t get the chance to engage with. The tour was given by a local artist who reiterated her desire—and inability—to travel, while also expressing her appreciation for this cultural exchange.

The open questions and community-led cultural infrastructural projects felt most promising, while the top down, brightly colored and attention-seeking interventions like Carlo Ratti’s yellow lowline(?) seemed more self-serving and sensational than in tune and collaboration with the rhythms and desires of the community. It also occurred to me that many snails had made this less anthropocentrically-used part of the city their home and seemed existentially put upon by the increase in foot traffic. Beginning to research Carlo Ratti’s practice a little further, I encountered a video for a project called Favelas 4D in cooperations with MIT’s SENSEable Cities lab that opened with a bunch of LiDAR scanned renderings of informal neighborhoods, talk of how to correct neighborhoods build without master plans and statistics about how many millions of data points could be captured per second. Standing on the ostentatious path between two streams of anxiety-generating traffic just above head-level, it was clear, without millions of data points per second, sweeping drone footage of virtual architectural renderings—and potted plants, that this was not a desirable area to stroll or linger. It remains to be seen if this kind of intervention will be maintained or appreciated when the Manifesta is over.

Swiss artist Ugo Rodinone’s contribution not a word not a thought not a need not a grief not a joy not a girl not a boy not a doubt not a trust not a lust not a hope not a fear not a smile not a tear not a name not a face not a time not a place not a thing wrapped the contested Tito-era socialist modernist Brotherhood monument to fallen partisan soldiers in Adem Jashari square in a shiny purple foil, and set off alarms for me (as a self-appointed and perhaps irredeemably naive arbiter of ethical internationalist exhibition-making). Its candy-bar like social media-readiness, glib call to ‘revel in the pure sensory experience of color, form and mass,’ and further confusing evocation of Beckett’s Watts, felt like a cheap intervention that offers more to the artist than any kind of meaningful engagement with the community and its complex history. In a counter-intervention, from a presumably local and anonymous artist, a small pink plastic backpack with minnie mouse prints on it was placed inside the foiled monument.

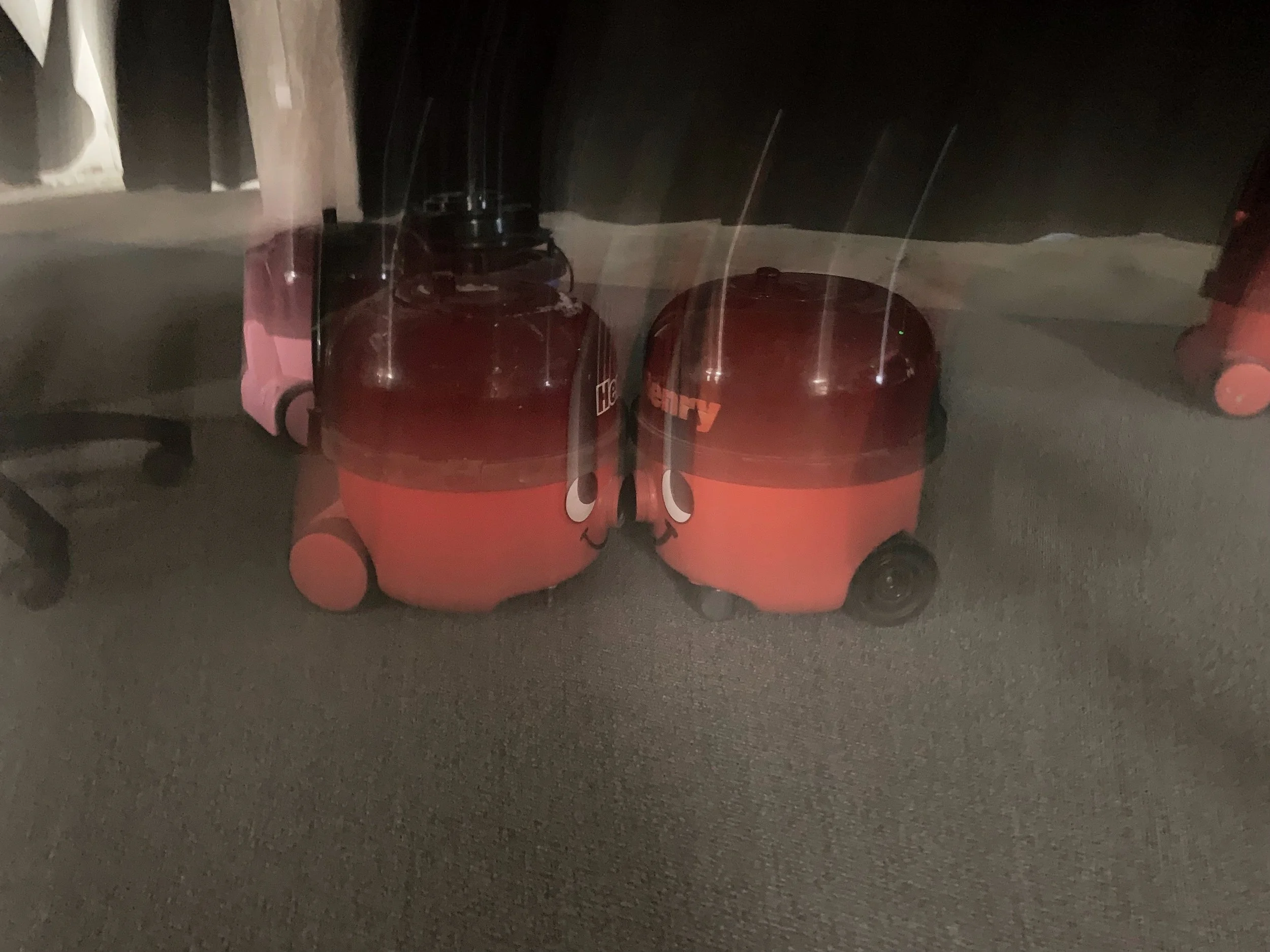

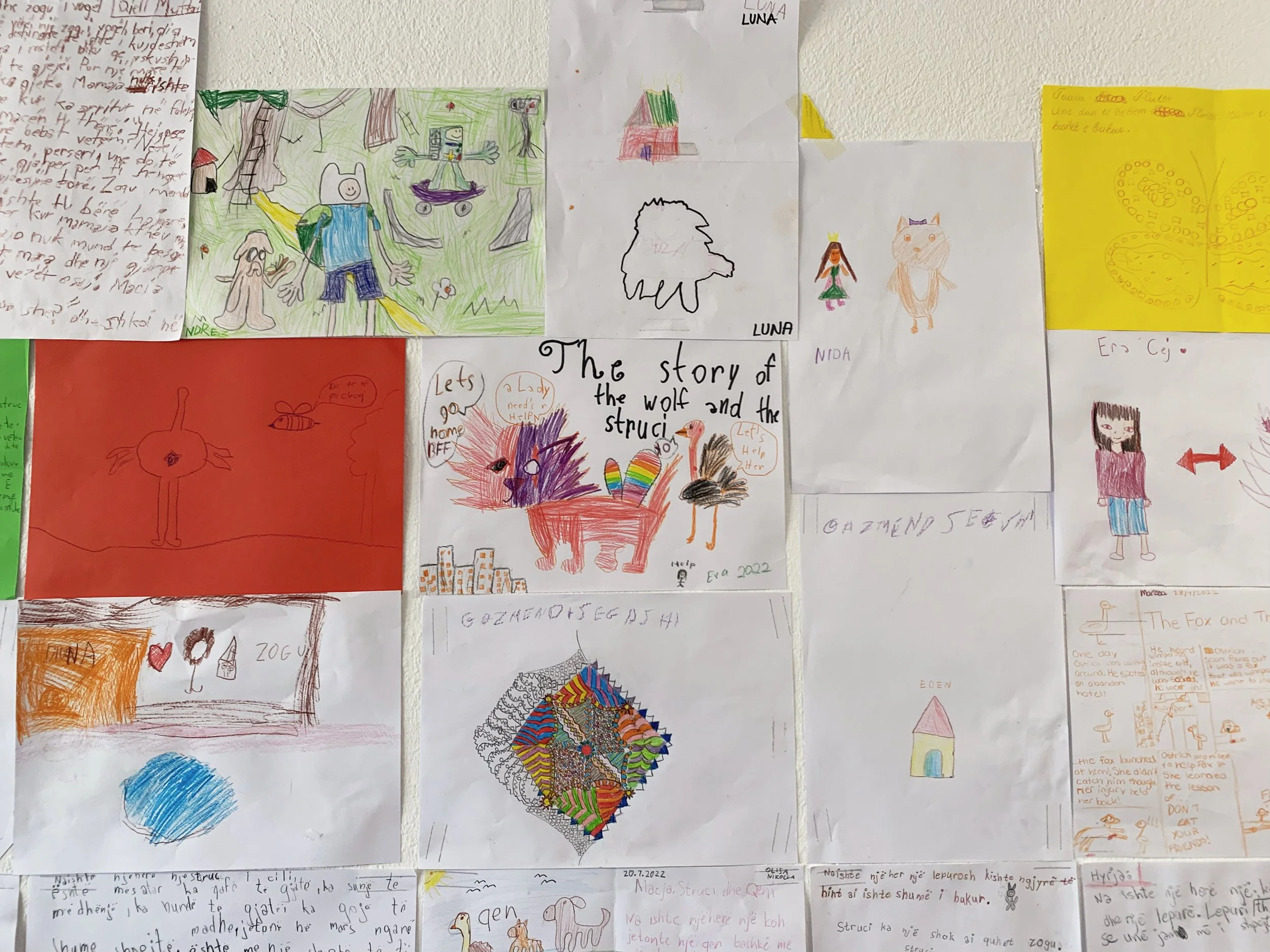

I generally observed a light irreverence towards the Manifesta proceedings from the Pristina locals, which actually felt quite refreshing. In one single-channel installation at the Grand Hotel by Larry Achiampong, concerned with the lives of migrant workers, a series of anthropomorphized vacuum cleaners were arranged around the room—in what I took as a choreography of alienation, and to which some youthful and bored invigilators rearranged into pairs that appeared to be kissing. A Kosovar curator and artist named Ardian Ajdini intervened in the Grand Hotel portion of the exhibition, collecting invigilators while performing hilarious and historically-grounded tours. Actually, many of my attempts to go look at art were derailed by Ardian and other new friends who would steer me towards local eateries like Baba Ghanoush and Tiffany’s where we would settle into long and art-ful conversations over delicious food.

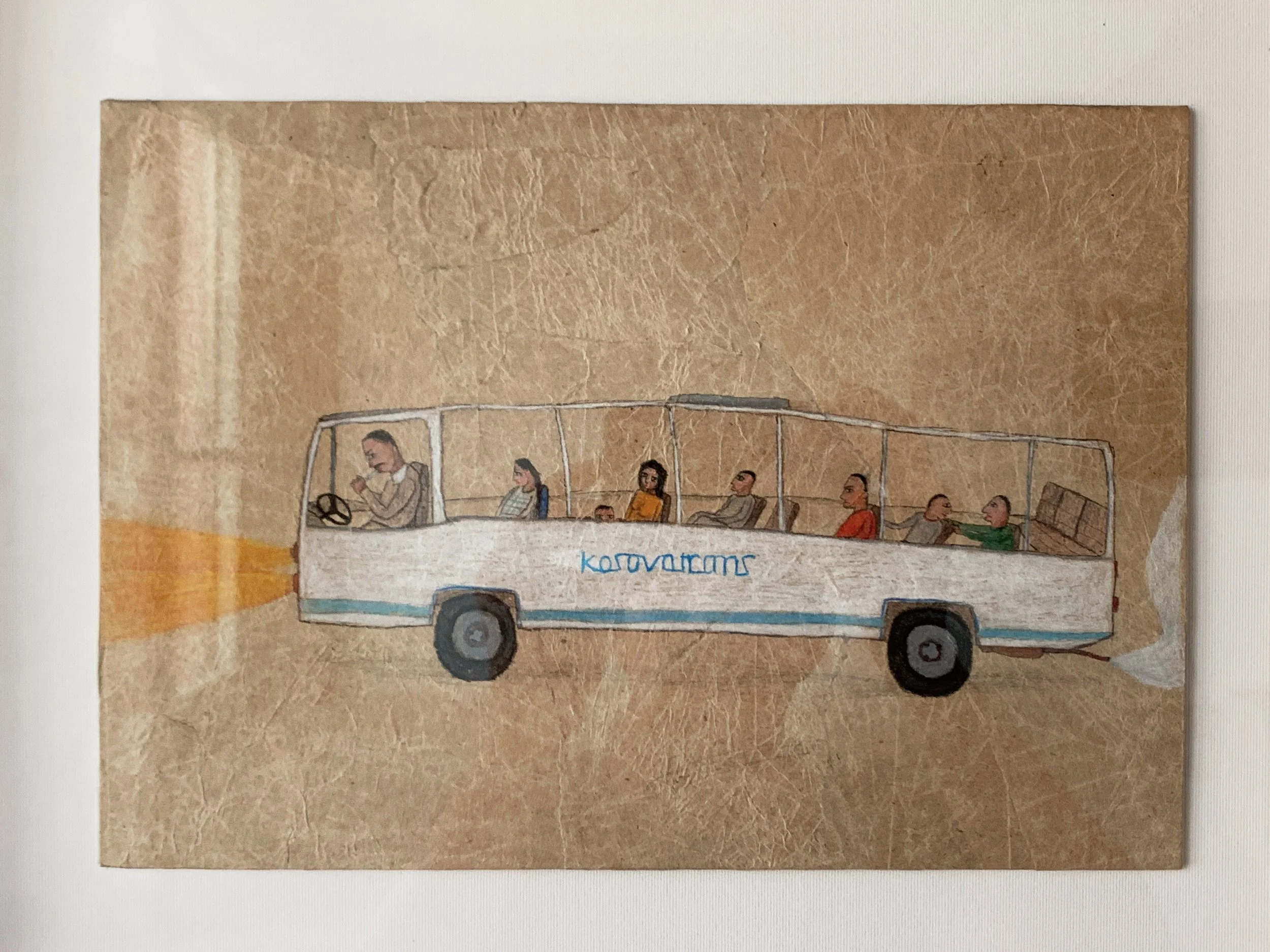

The interdisciplinarity of the other interested visitors I encountered provided many insights and break-away conversations that continued over meals and are continuing in correspondence. In advance of the trip I spoke with my friend Lani Maestro, who I met in Venice when she was exhibiting in the Philippines pavilion. I mentioned my dissertation and its areas of focus, and Lani began sharing some of her experiences and insights from the Havana biennials that she participated in. I got the sense that it was formative and significant and her fond recalling affirmed what curator Gerardo Mosquera described as ‘the first global contemporary art show ever: a mammoth, uneven, chaotic bunch of more than 50 exhibitions and events presenting 2,400 works by 690 artists from 57 countries. The biennial’s variegated structure made it a true urban festival, a pachanga that involved the whole city. More importantly, never before had artists, curators, critics and scholars from Buenos Aires to Kingston, and from Brazzaville to Beirut and Jakarta met “horizontally.” (Basualdo et al., 2010). Of course this event was experienced in many different ways; whether by the Cuban youths pulled off the bus tours organized for the artists, or the government officials who felt they lost control of the narratives and began internally curating future editions more conservatively, or a younger Lani, given an early career opportunity and a special prize, in the form of a check from Castro, that afforded her a ticket back to the Philippines from Canada to see her family. These unfolding histories and my own intersections as an absent spectator provide a small window into the manifold ways discursivity, effects and affects transmigrate over time, taking on new valences. Like art, value is provisionally co-determined by objects, subjects and times. Downstream from Heraclitus, Anna Tsing offers that ‘Rather than scalable science, the place to start is critical description of relational encounters across difference.’ And continues in her On Nonscalability essay that ‘because relationships are encounters across difference, they have a quality of indeterminacy. Relationships are transformative, and one is not sure of the outcome. Thus diversity-in-the-making is always part of the mix. Nonscalability theory requires attention to historical contingency, unexpected conjuncture, and the ways that contact across difference can produce new agendas.’ (Tsing, 2012)

It is from an age of advanced uncertainty, or anomie, and the desperate fundamentalist reactionary compensations, that I offer a definition of art and life as provisionally co-determined by subjects, objects and times. Beyond that, it is a shared affective, ethical and epistemological project of speculative codetermination, and one I believe that benefits from the kinds of dispositions that for whatever reasons have been neglected in the modern period and its dominant narratives. We could gesture towards these dispositions under the aegis of uncertainty, openness, playfulness, experimentality, flexibility, generosity, kindness, plurality and hospitality, which are distinct from the prevailing dispositions of certainty, force, greed, exclusion, rigidity and violence. It is in SICAS where I’ve found that one is more likely to encounter these former dispositions, which I see as conducive to practicing relations that aid in the decolonization of time, dissolution of borders, reimagining of socioecological space, and the plural flourishing of more-than-human dignity, moving us towards the everywhere perennial of quotidian kindness and beauty.

References

Arruda, L., Nagle, R., & Honnef, K. (2022). News. documenta. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://www.documenta.de/en/news#news/3042-documenta-fifteen-halfway-point

Basualdo, C., Niemojewski, R., Filipovic, E., van Hal, M., & Øvstebo, S. (2010). The Biennial Reader. Hatje Cantz. 9783775726108

documenta11 - Retrospective. (n.d.). documenta. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://www.documenta.de/en/retrospective/documenta11

documenta fifteen. (2020). documenta fifteen. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://documenta-fifteen.de/

Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Allen Lane.

Han, B.-C. (2022). Hyperculture: Culture and Globalisation (D. Steuer, Trans.). Wiley.

Ngai, S. (2020). Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form. Harvard University Press.

Panel discussion with Pavel Borecky, Shpat Deda, Shpresa Loshaj in conversation with Prof. Ilir Rodiqi – Manifesta 14 Prishtina. (2022, August 19). Manifesta 14. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://manifesta14.org/event/when-you-talk-of-the-water-panel-discussion-with-pavel-borecky-shpat-deda-shpresa-loshaj/

Smith, T. (2022). Curating the Complex and the Open Strike (S. H. Madoff, Ed.). MIT Press.

Tsing, A. (n.d.). On Non-scalability. The Scalability Project. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://scalabilityproject.org/

Verheaven, J. (2021, March 22). 7. Symposium: Constructions of Time Still and Moving Imagery – Filipa Ramos. YouTube. Retrieved August, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WMTsGn_mRg

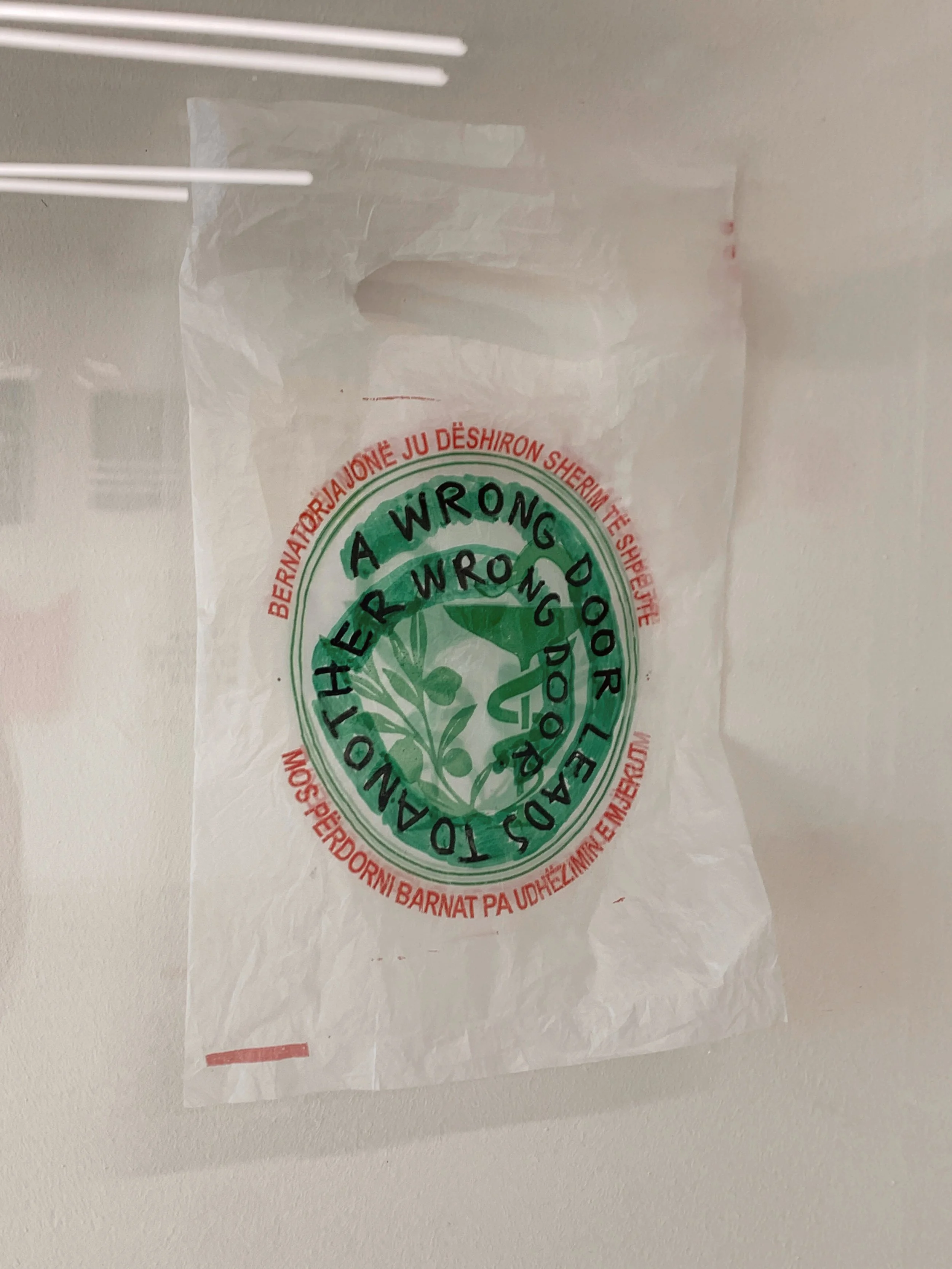

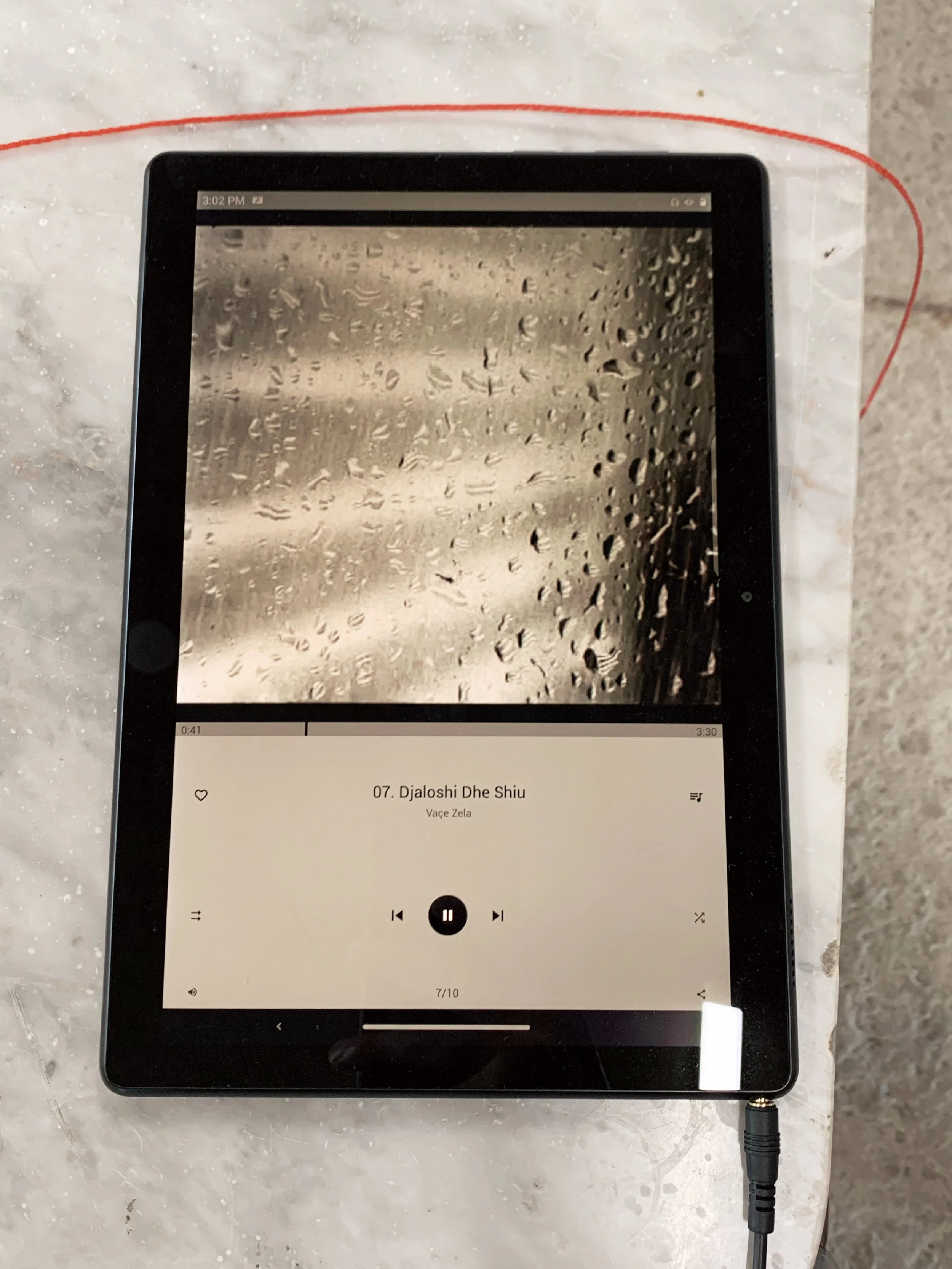

A film essay of my time in Pristina during Manifesta, interspliced with Kosovar and Albanian pop music from a black market USB drive.

Notes:

My friend, begins my inner voice

The difference between yeah yeah and yeah yeah yeah…

In the notes section where I tried to quickly thumb the art world is colonized by Protestant bureaucrats and data scientists, I ended up with Art world is [lettuce emoji] niz e by

Heavy eyelids, long lashes and warmly incredulous eyebrows. Of course, a visage that breaks into a hard won cartography of long laugh lines.

Black and white film at the grand hotel. You see these essentialized tropes of communitarian collective ideals and solipsistic bourgeois alienated narcissism and they both sound so unfun, what a false choice and poverty of imagination. And what’s more, these abstractions have little to say about the drive to power and how those inclined towards power make use of whatever ideology is expedient to its consolidation. The same in the Vatican as Silicon Valley, Russia and the US.

Touching the suture between myself and the world.

Antibiotics are the nuclear bombs of microbial agencies.

In Jacob Lund’s recent anthology the changing constitution of the present, organized around the nebulous conceit of contemporaneity, or disjunctive temporal overlap, partially and novelly apprehend through networked technologies, Lund offers a reading of Simondon by Paolo Virno, forming a kind of miniature historiography of contemporary thinking on contemporaneity usefully elaborating the transindividual drift of meaning. To apply this transidividuation, partially, to Pristina Manifesta...

Art is rarely valued until it is valorized by capital.

Chapter on gameification - money as game with increasingly convoluted rules. Money as etiquette, as in primarily symbolic and valueless outside of its command over peoples imaginations. The real value of things (and time) is obfuscated by this symbolic order.

Old stories as time travel… how beautiful...

This sensitivity to the polyphony of temporalities, transindividuation

The young architect who said the locals were going to the observatory when it rained because it sounded beautiful on the roof. Nevermind there was a temporary AI art video game installation.

Young Slovenian art students going to thrift stores. We took a walk and talked about art schools and biennials. They showed me their work, a studio turned in a friendly social space, with some curious objects, and a kind of kintsugi done on a concrete floor.

Sway

A period of intense traveling with the sense that I was obliged to understand this context as much as I could before enjoying myself at all.

On the bus to Tirana I wanted to listen to weirdo hip hop, microfiche, sudden death, tiptoe. Maybe because of all the Albanian rap. Quelle chris at cafe oto and fresh boreks at the gas station

Here is a nice exercise. Imagine everyone around you is connected to unimaginable hardship and suffering and see how that changes your disposition towards them. Then, let that feeling and disposition grow as wide as possible to every single thing around you.

The snails after the rain give me anxiety

One cab driver turned off the meter and overcharged me when I said I didn’t like George Bush and another lowered the price and came along with me to the bazaar.

Docent named migration who was kind and explained the Lawrence exhibition to me and asked about my expectations about the bazaar and then how I experienced it.

Rumors everywhere. Streets with no names. Police building. Spa in grand.

Mergim name. Migration.

Promenade and cafe culture as technology. Got into a minor spat with a local musician about Elon Musk and greenwashed capitalism. Ended up saying, publicly, Mother Theresa blvd is sexy! in response to his comment that Elon made electric cars sexy.

Arrived (everywhere) as a student. How special, slower time, pedestrianized streets.

Everyone keeps saying how kind the people are in Pristina, and it’s so true. It’s stunning and makes me question my bad social habits; irony, impatience, indifference…

The kind of crew that lament visa issues that prevent them from going to burning man with Larry Pages camp—sex tent? He actually came up twice that day the other time in anecdote about his Fijian lockdown where he disallowed the staff to go home to visit their families on nearby islands.

Department of cultural contamination?

The haunting of the photos of the hotel’s former grandeur. The piano music and the docents singing together with the hotel staff. The way the invigilators get bored and rearrange the art.

The Botox injections, dua lipa-fication, government digitalization initiatives.

Notion app?

De-severence

Instagram as exoskeleton

They need to do core samples to understand the real history of the building, the center for narrative practice.

Histories changed for political reasons. Library might have been a prison? Or a police station? Carbon dating. Spa as gas chamber.

Someone said streets had no name. Ask dean. 3 administration changes during the planning of manifesta. Museum was a prison. Grand hotel was military base, paramilitary, in the nineties.

Parking lots are a favorite thing of capitalism said the tour guide in the former public stadium, now partially privatized stadium. Brick factory was full of dead cars. The greenway couldn’t work because of all the cars. The roar. Low line.

Conversation with a graphic designer from Leipzig and a psychotherapist from ville urbane who wanted to better understand her clients background and also is part of a film collective that programmed events with apichatpong. Two art administrators that work for the Flemish government, joined them later at tiffany’s. The young bitter and hilarious docent was saying she loved it for all the stories that came to her while she is not able to travel. A lot of local visitors coming thru.

Not having service or electricity all the time causes these moments of collective improvisation and possibilities.

The maintenance guy in the philosophy department library rescuing Marx books from the purge and giving them to a sympathetic professor.

The airbnb host had ‘Ora’ as their wifi password and seemed impatient with my interest in art. I walked up the 12 flights of stairs in the centrally located flat with a nice terrace vista where common swifts would careen through the air in the mornings and evenings.

I feel better about staying in airbnb’s when they’re on the top floor of a walk-up with no elevator.

Interesting first encounter in a beautiful building and courtyard with a thoughtfully curated library and informal talk in the garden, magpies flying overhead.

The talk felt largely centered around local artists wanting more resources. Seemed mostly attended by the local artists’ peers, maybe friends, who seemed interested in accessing some of the capital that manifesta was bringing in. All seemed interested and inspired by the energy and wanted to continue utilizing the spaces that manifesta occasioned. I’m concerned it skips those who are not internationally aspiring artists. Still the library’s are open, the sites are well labeled and I’m curious to know more about outreach. I felt myself getting bored with the art scene micro politics and a form of collectivism that felt ultimately individualistic. The collective as a means toward accessing attention, opportunities and space. That said, the infrastructure and resources are public and social. A lot of the other local artists basically kept asking variations of can I get into this or that collective? and can I access this or that space? This gets towards the core of some big political issues and biennials in general.

The filmmaker bristled and then erupted with resentment for having to perform victimhood, though he is clearly in a different class and very international. I see this a lot. Our conversation turned towards defining the real political stakes, dissolution of borders, rights to mobility, access to a life with dignity.

Tristan, an actor and writer of the translated short story collection Richard Gere was Here came up on handsome bicycle with a clown horn and sat down introducing two people at an adjoining table as my ex and her ex, perhaps suggesting the intimacy of this local scene.

Lots of touching, clamorous glasses and large plates of meat.

I leave quietly in the transition between venues and stop at a late night bakery for an oily layered dough pastry and some yogurt. It costs almost nothing.

I’ve been surviving on yogurt, the more wild the better and think how museum culture is like pasteurizing and then adding synthetic probiotics.