29: Graduation Show

I kind of love how the graduation show happens in July, almost 6 months before the end of the 15th month course. It’s like we can get that out of the way and focus on other important things. This inaugural Art & Ecology course is experimenting with building in an inter-cohort transitional term with the incoming group which seems like a great idea.

The Sianne Ngai becoming-ergon of the parergonal discourse of evaluation library and tea room has been a rewarding learning experience so far. It has occasioned a lot of thinking and interesting conversations. The work—so to speak—spills out into every part of my life and it’s difficult—and not really desirable, for me to try to define the boundaries.

At this juncture, I’m interested in finding a home for the library. In the course of describing what it was I was trying to do with this project, I found myself recursively describing the feeling of being in Francisco Toledo’s IAGO in Oaxaca city. How much I loved the art-book reference library, beautiful courtyards and exhibition spaces. This has helped me clarify and articulate the want to participate in the creation and maintenance of intentional libraries that share a similar spirit.

I have been in and out of the space since the opening last week. Dropping off new books, objects and images and having conversations with people. I got a photo book about a trip to Ladakh that I had coveted in the Yvon Lambert bookshop in Paris some years ago from a Kensington charity shop, along with a few other titles that I cycled back to London fields with in my backpack and brought with me to the library the following day. I came across a folio of badger ephemera at the boot presumably collected over many years that was delightful. I found a beautiful collection of family photos and another artist and I went through them speculating about their former owners life. She and her partner came to visit me at the library and brought some more information and stories she gleaned at the same market a few days later. Friends came and brought gifts, cucumber melons and homemade pesto.

I uploaded the full length version of the Passionfruit film and applied for a job at MoMA.

Dear MoMA,

This position brings me a great sense of complementarity and excitement.

My relationship to image-making has been life-long, highly variegated and rigorous, both as practice and in research. I’m currently completing my MA in the inaugural year of Goldsmiths University of London’s Art & Ecology program where I’m working on a dissertation entitled Biennialization and hyperculture; the decolonization of time, dissolution of borders, reimagining of socioecological space, and plural flourishing of more-than-human dignity, or, the everywhere perennial of quotidian kindness and beauty. The dissertation looks at trends in what I term Seasonal International Contemporary Art Surveys (SICAS), in particular Documenta, with an emphasis on the Enwezor, Bakargiev, Szymczyk and Ruangrupa editions. It looks at models for generating knowledge, discourse and alternate socioecological relations commensurate with planetary entanglements and offers hybridity and mondialité as states and dispositions that redress the hierarchies and assumptions of the modern period, with its oppressive axioms, persistent binaries, taxonomies, erasures and exclusions.

For this cover letter I thought I would give a little biographical information as well as some relevant experiences and particular interests. I grew up in a small apartment in Manhattan in the building where George Plimpton lived and published the Paris Review. My father has since moved to 53rd street, a few blocks east of MoMA. I went to 10 schools around NYC including Bronx Science, the United Nations International School, and the Institute for Collaborative Education (ICE) where I studied with the singular Meryl Miesler and went on to run one of the affiliated Greenwich Village Youth Council’s community centers in Nolita, doing afterschool education for kids 8-18 from the lower east side. Simultaneously, I was the music editor for a culture journal and active in downtown nightlife. In my early twenties—literally after seeing Frank’s Americans at the Met—I bought a 5D Mark II and traveled around America by car for the better half of a year learning and making images.

I realized through this creative process that the networked image at this stage of visual culture, and the reckoning with asymmetries of power in the unfolding histories of colonization, had created almost entirely different conditions for image production and reception. This changed my focus and practice, though the lineage where one could situate that kind of project still holds an affectionate place in my heart; Lange, Evans, Frank, Winogrand, Sternfeld, Meyerowitz, Hatleberg, and so on. I have a great love for street photography; Levitt, Parks, Bresson, Arbus, Maier, Shore, Leiter, (Raghubir) Singh, and Iturbide to name a few. Especially photographers for whom this work, for historical reasons, could never have been a vocation and nevertheless persevered through their lives as an epistemological means. From this lineage I recognize a school of early social media street photographers that constitute a distinct period, or even renaissance in street photography that in my measure remains under theorized and appreciated—though not without some thorny issues and questionable practices. I’m interested in exhibition-making that takes up complex issues through their historical immanence with rigorous research and polyvocal discursivity. And also how to distill those ideas into forms that can be assessed by broader publics.

More presently, I’ve been fascinated with how images circulate consequentially through, and around, platform capitalism (and their theoreticians like Hito Steyerl, Trevor Paglen, Jonathan Crary, etc) while totally reconfiguring and in some instances obviating the evaluative tools and theoretical frameworks that were popular in the modern period—including those of individual authorship and private property. I’m taken with the research-based archival turn and the social media-influenced works of multisource montage, à la Arthur Jafa and Kahlil Joseph. I’m also very interested in accessible alternative archives, like the Arab Image Foundation and public domain archives that are available for research and poetic speculation.

I’ve been studying adjacent to Forensic Architecture at Goldsmiths and have found their interdisciplinary approach to social justice to be a great contribution to the tradition of image-centric and evidentiary activism. A tradition which can be traced back to the near inception of photography, and whose more recent resonant protagonists for me include; Farocki, Sekula, Mieselas, Edmund Clark, and Armin Linke. I had the pleasure of spending some time with Yuki Kihara in Venice just last week and their multifaceted and research-based approach to photography-centric, performative and politically-committed installation and publication is an exciting form for me. Diana Markosian’s recent Santa Barbara is another compelling example making use of this formal range.

I suppose at this historical juncture, it's hard to separate the production and use of images from any other art practice—let alone any other field, while images function in an exponentially multiplied proliferation of roles. This makes it a thrilling time to think with a place like MoMA about how to apprehend and address this epochal turn in meaningful ways.

I’ve found anthologies like Walead Beshty’s Picture Industry: A Provisional History of the Technical Image foundational to my understanding of photography. I’ve been thinking with Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s Lives of Images series, which features many theorists dear to me. I recently saw Erika Balsom’s survey of moving image No Master Territories at the HKW, where I’m consistently impressed with the skillful production of exhibitions, parergonal events and publications.

I locate the contemporary photography conversation largely in what could broadly be termed a remediative turn that includes themes and methodologies of justice, pedagogy, journalism, therapy and care, in accordance with the urgencies of anthropogenic ecocide. As such, this work takes on an ethical imperative at the institutional level. And at the same time, I have deep and abiding love and respect for the ambiguous, ambivalent, uncertain, ineffable and beautiful, which Elaine Scarry—among many others, suggest are closer in distance than we might imagine.

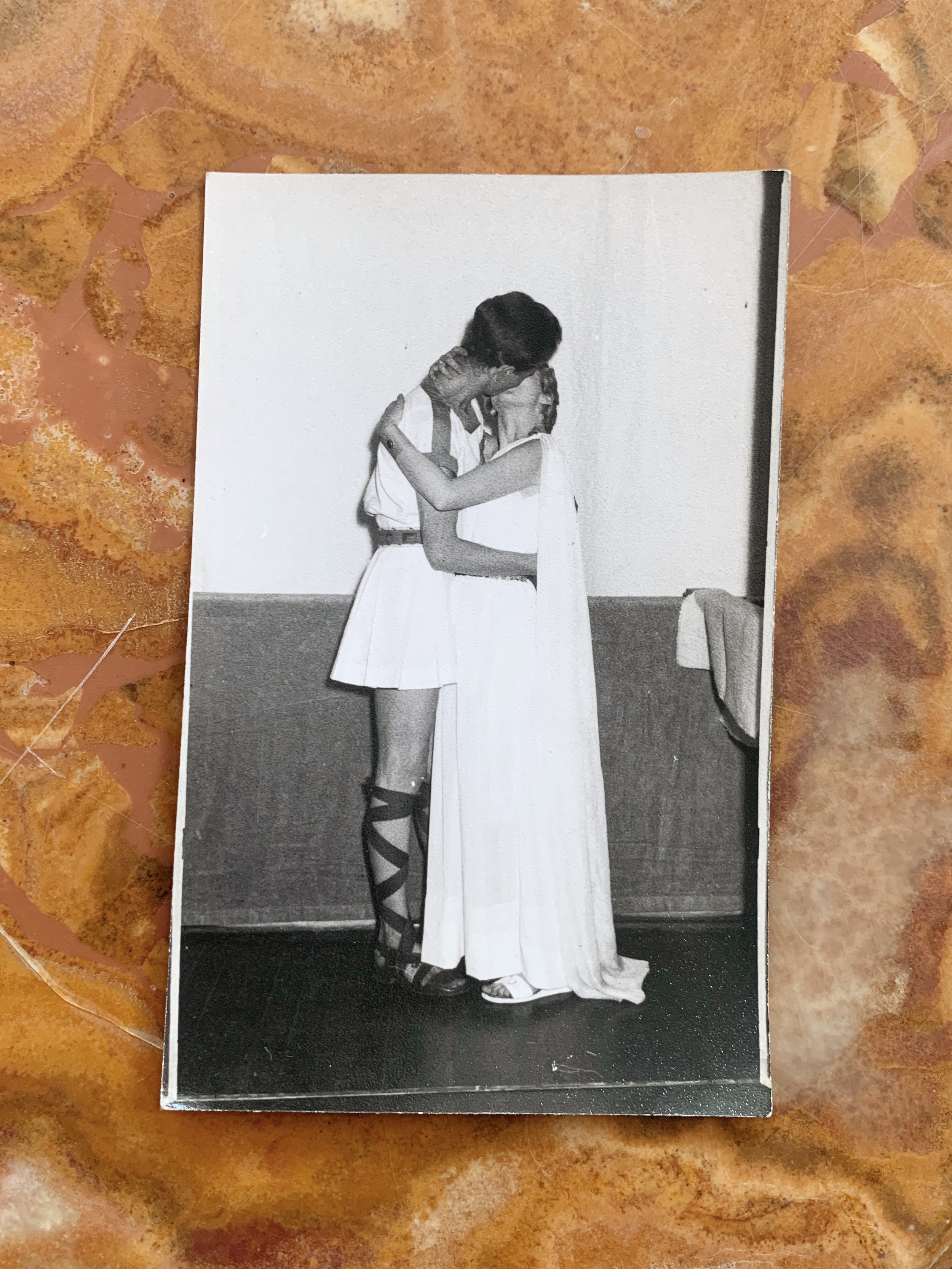

As far as my personal tastes, I have an extensive and idiosyncratic collection of 20th century vernacular photographs which you can see a small sample of at www.ahurei.one paired with musings on the surviving fragments of Heraclitus. I love Luigi Ghirri as a photographer who can remind us of the perennial wonder and transcendent beauty that is ever present, even when the conditions allowing for its noticing and flourishing are so constrained and unevenly distributed. Taryn Simon is an artist who changed my conception of photography and its possibilities. And Malick Sidibé’s Nuit de Noël comes to mind when I think of my favorite photographs.

I love artist books and regularly attend the international small press art book fairs, where much interesting work and sociality coalesces. Photography as a meditative act, in a distracted world, and as a mode of quotidian communication, is where I’ve arrived in my own practice. And as a mnemonic surrogate. I’ve documented my daughter to a degree likely impossible before the advent of digital technologies, and at 13 years old, she shares with me a distinctly generational perspective and fluency in modes of image making and circulation that require the ongoing questioning of received ideas and assumptions about these fluid and prismatic media.

I have been archiving the work of the German-born, California-based photographer Ilka Hartmann, who photographed most of the significant social movements in California in the latter part of the twentieth century. Stanford is archiving the bulk of her oeuvre with emphasis on well known individual activists and I’ve been focused on a small and particular body of work in its relation to a distinctive town we’ve both called home.

It would be wonderful to be at MoMA at this juncture in my life, learning with their history, and working on collaborative projects of significance with people I greatly admire. This includes Remi Onabanjo, who I’ve had the great pleasure to get to know through my partner who is a dear friend of hers, and Clement Cheroux who I had the pleasure of meeting through Sophie Calle during his time at SFMoMA. The new photography series, rotational, thematic and retrospective shows have been a great pleasure for me over the years and I would love to care for and participate in a supportive and collaborative role.

I’m preparing this week for my final show at Goldsmiths where I’m offering the Sianne Ngai Becoming-ergon of the parergonal discourse of evaluation Library and Tea Room, that will exhibit a number of artist books and texts that relate to socioecological concerns as well as an online archive I’ve created in response to art exhibitions around Europe, along with many found images and objects collected during the same period of study. After that, I’ll be completing my dissertation in a low residency capacity to be delivered in September. I’m available to start as soon as needed and I have a place to land in New York, quite a short walk from MoMA.

My website is www.perryshimon.com and my most recent project is ritualsintime.space which include much writing about art.

Thank you kindly,

Perry

Biennialization and hyperculture; the decolonization of time, dissolution of borders, reimagining of socioecological space, and plural flourishing of more-than-human dignity, or, the everywhere perennial of quotidian kindness and beauty.

Perry Shimon, MA Art & Ecology, June 2022

The major international durational and discursive survey of contemporary art is a variegated and contested site for the rehearsal of socioecological relations and cultural exchange becoming-commensurate with a scale of concerns responsible to an interdependent planet. Looking at particular situated instances of critical quinquennials, biennials and the like is an instructive practice for reimagining relationships to knowledge production, time, labor, place, education, and leisure, while identifying practices worth developing and reproducing, including the occasioning of ongoing symposia, performances, installations, libraries, and other forms of in person and online sociality, as well as online and print archives and publications.

As contemporary art, modeled on an eurocentric and market-driven approach, inextricably linked to colonialism, has reflexively included into its machinations an autocritical tendency as well as assimilating social and relational practices into the ocular-centric Visual Art Exhibitionary Complex (Terry Smith) and coevolving with the precaritization of labor resulting in the turn towards platform capitalism and the ever encroaching financialization and entrepreneurialization of all forms of life—particularly under neoliberalism, it has opened up durational occasions for critical reflection on the production of these practices through the extended biennial form, which has rapidly proliferated since the latter half of the 20th century and is characterized the production of live and discursive events which have unsettled the hierarchies of received exhibitionary teleologies—suggesting what Sianne Ngai formulates as the becoming-ergon of the parergonal discourse of evaluation.

The pedagogical turn in contemporary art, owing in part to internet-restructured forms of knowledge production, consumption and contestation in concert with the vocational exodus from the austere conditions of both academia and journalism, has further advanced the biennial as a site of discursive exchange and knowledge production, and often with a rigorous criticality articulated transversally through disciplines and contexts. Though perhaps more than transversal in effect, it is an articulation of a hyperculturality that ‘de-facticizes, de-materializes, de-naturalizes and de-sites the world.’ (Han, Hyperculture p79) distinguishing itself from the modern tendency of essentializing regional cultures—prerequisite for thinking trans- or inter- relationships to begin with. The peripatetic class of art elite is a conspicuously pronounced articulation of these effects that can also be readily observed in the hypermarket diversity of globally connected locales, and the windowed ontologies of tabular internet browsing.

In an ever-implicating globalized and interconnected world of collapsing distance and horizon, in the midst of cascading socioecological crises, we find an imperative to create and gather in de-virtualized social spaces for apprehending and addressing our mutual concerns. Additionally, the practice of this kind of (unevenly accessible) planetary being-with produces affirmative models for reimagining public space and relations, with an abundance of cultural offerings and the conditions for what we might call reparative sociality. What is abundantly clear in any conversation about this kind of exhibition-making, is the necessity to better distribute time so that the working class and precariat can participate in not only the concerned and aesthetically manifold sociality of this kind of exhibition-event but also, and more significantly, to determine the use of their time towards the most meaningful relations and vocations in their lives.

The term ‘biennial’ has come to stand in for a spectrum of large-scale international durational exhibitionary happenings that occur with increasing volume around the world. It is a misnomer, as in many cases they happen with differing frequencies and the reference to the time between their presentations doesn’t begin to account for their qualities. I offer in its place the Seasonal International Contemporary Art Survey or SICAS. Seasonal connoting their time-bound durations and recurrent structure, and survey including the discursive function left out of the visually privileging exhibition.

The documenta, a quinquennial survey, is a useful case to sketch out some of the claims and potential horizons of the form. Inaugurated after the second world war in Germany to exhibit formerly censored ‘degenerate art.’ The documenta has grown over the subsequent 15 editions to rehearse a number of different formats, methods and modes of production and distribution. Enwezors 11th edition marked a significant departure from the occidental focus of previous editions and the general trend towards this format has occasioned differentiated forms of multilateral hybrid cultural exchange across the world. It was produced in 5 different locations with a range of artists included from global south, if not with familiar forms dedicated by market and convention. Coterminously, roving SICAS like Manifesta moved east to peripheral European contexts and a host of SICAS in the global south endeavored to focus on concerns outside of or resisting Euro-North American chauvinism, including Sao Paulo, Dhaka, Istanbul and Havana.

SICAS are highly variegated in their production and distribution and have justly been criticized for their neoliberal dispositions, interventionism, easy compatibility with tourism initiatives and at times collusion with oppressive state apparatuses, and less directly—though not unrelated—neoliberal expansion in the deregulatory, restructural modes outlined in Keller Easterlings Extrastatecraft. The twin engines of deregulation and art-washed beautification are often a solicitation to capital or deflection of state violence. This compromised state, which has been well documented by critical historians like Charles Green, Anthony Gardner, Maria Hlavajova, Simon Sheikh and many others, does not obviate the potential horizons of these survey-forums, which are likely immeasurable in their impact. Simply looking at one documenta, especially one located in multiple cities, for 100+ days of live events, installations, screenings, publications, and so on, demonstrates the impossibility of the apprehension and synthesis of the event which is experienced in so many ongoing, unfolding, anasynchronous ways, as well as through the tertiary and further refracted speculative possibilities collaborated with what Filipa Ramos terms the absent spectator.

An inventory of the constituent elements required for occasioning art with the capacious, partial and fugitive definition offered here, can most basically be understood as subjects, objects and time, the latter of which is of primary concern and where I locate the stakes of this thesis. This broad understanding of art invites the open question of conditions favorable to art. A city like London, where I’m currently residing, has in excess, many of the qualities favorable to art and the offerings one encounters in SICAS; namely the ongoing superabundance of social, aesthetic and discursive events. It suffers from an austerity of time among the working class and precariat and simultaneously an excess or wealth among the elite and more time-privileged, for whom it is impossible to enjoy the superabundance accumulated through the violent dispossessions and subjugations of colonial empire.

These themes are taken up recursively in many SICAS, which also tend to feature fertile interdisciplinary and transmedial assemblages that, to my mind, are without comparison. Arguably, the critical biennial is the site par excellence for explicitly redressing violent histories of power relations and rehearsing the otherwise. Here it might be useful to examine the word rehearse, which is popular in the contemporary art lexicon and in my usage connotes the preliminary suite of gestures towards the counter- or alter- hegemonic from, from which to build more lasting physical and social—or perhaps what Irit Rogoff calls spectral—infrastructures, that is to suggest, the habits of mind or axioms that condition and choreograph our relations.

Another infrastructure of great interest, that we might term deterritorialized, or perhaps simply a truly territorialized—in the broadest sense—infrastructure is e-flux, the central nervous system of the contemporary art world, not insignificantly started by artists, and holding some similar tensions of a market-dependent position seeking to overcome its contradictions and conditions towards a more sociologically just world.

Notes for Edgar,

Hey, just quickly put this together, still in the glow of the wonderful conference you’ve convened with Ofri and Murat. You can see towards the end where some of the thinking shared this weekend has found its way in…

I plan to elaborate some these core positions and focus on particular SICAS of note

Also bring in Graeber and Wengrow’s Dawn and perhaps Campagna’s cosmological thinking—tempering it with its western colonial legacies and contemporary excess of what we could call financialized planetary technocracy—to look at dispositions towards cosmological openness and how that sometimes feels welcome in SICAS. I’m calling this cosmological promiscuity.